Mechanical Ventilation Was Not The Proximate Cause of Death In Early Covid - Part 3

Here I explore the nuances around the use of mechanical ventilation in 2020. It is not a simple story, contrary to many like Elon Musk that believe "the ventilators killed patients."

Mechanical Ventilation Practices During Early Covid In The U.S

In Part 1 and Part 2, I made arguments that most of the U.S hospital deaths early in the pandemic stemmed from the lack of corticosteroid treatment (or any treatment) being offerred to patients which resulted in unprecedented hospital mortality rates.

A few key points to further support that argument:

Prior to Covid ever happening, most if not all patients who died in the hospital did so on a ventilator, but for some reason, in Covid, many began to blame the use of mechanical ventilation as the proximate cause of death.

Dying on a ventilator has always been the reality of hospital deaths. If a patient develops a life-threatening illness and the treatment approach doesn’t work or the patient presents in too advanced of a state or is refractory or poorly responsive to treatment, they deteriorate onto a vent and then deteriorate towards death on a vent. Pretty standard trajectory for any hospital death. Doesn’t mean the vent "killed" them just because they died on a vent. Nearly every patient who dies from critical illness does so on a vent. Conversely, anyone with severe critical illness who responds to treatment will be successfully removed from the ventilator. Ventilators are support systems, not treatments, and do not appreciably injure lungs when used correctly.

Mortality rates began to plummet after corticosteroids (and other immunosuppressives) were systematically adopted despite the continued use of ventilators

Now, I am not saying that mechanical ventilation was not inappropriately used, nor that it did not contribute somewhat to increased mortality rates, but the mortality rates were much, much more driven by the lack of effective treatment, again, as explored in Part 1 and Part 2.

Those posts largely argued that the systematic use of “supportive care only” practices and avoidance of corticosteroids was the principal cause of mortality in the “first wave.” However, there were multiple other contributing factors which I did not focus on. One reader wrote to me privately (an experienced nurse) and shared with me her traumatic memories of that time, reminding me about the lack of properly trained nurses and physicians in charge of the critically ill and the systematic avoidance of going into patient rooms by not only those staff but also consultants, radiology and EKG techs, ultrasonographers, physical therapists etc. Also the ever-shifting and burdensome PPE policies making nursing care more difficult than it needed to be.

Compounding this situation was the lack of family visitation. That probably outweighed the harms of all the rest, as families are, and have always been, a patients best advocate when critical information about a patient is overlooked, or critical aspects of their care are underemphasized or flat-out forgotten, or the physician is not particularly skilled, all events which are unfortunately not rare.

But mechanical ventilation use was also a contributing factor, albeit in my mind, a minor one, so lets analyze the issue of “inappropriate use of invasive mechanical ventilators.”

The inappropriateness that I observed was due to “too early” initiation in the course of a Covid patient’s illness. However, again, even if “too early” mechanical ventilation caused harm (and it did), if effective treatments had been offerred after intubation and admission to an ICU, death rates would have been far far less.

The reason for this is that if you do not treat critical illness correctly, patients almost uniformly die from critical illness (conversely, many outpatient infectious illnesses are easily handled by our immune system or simple anti-viral treatments, but once in critical illness (i.e single or multiple organ failure), it becomes almost impossible to recover without specific and often aggressive therapies. This is one of the reasons why I liked critical care so much, sometimes described as “general medicine on steroids.”

So, what caused the proliferation of early mechanical ventilation?

Some argue that it was due to perverse financial incentives that benefitted the hospitals bottom line or that providers around the world wanted “to kill patients.” The latter is still absurd to me (at least the idea that the average physician did so willingly and consciously) and financial incentives such as highly increased reimbursement rates for patients on ventilators have been a reality for long before Covid ever happened. I would instead argue that intubating early was not from explicit policies recommending early intubation but more from a lack of explicit policies or teaching which warned away from early intubation (same thing perhaps?)

But here is another point - unless you have been in a situation where a patient under your care is exhibiting declining oxygenation or increasing respiratory distress despite often maximal oxygen support, you cannot know the stress of that situation/decision in terms of having to rapidly balance the competing risks, benefits, and alternatives in deciding for or against initiation. It is a difficult decision in many types of respiratory failure, but especially so in a novel disease whose trajectory or responsiveness to therapy was initially unknown.

Being on the front lines, I saw early intubation being practiced out of ignorance and fear rather than policies or financial incentives. I should know because I was the Chief of the Critical Care Service at a major academic medical center at the time (the University of Wisconsin).

I was also the Medical Director of their Trauma and Life Support Center (we called the center “the TLC” for short but basically it was just the name for the main ICU at UW). I was also one of the more experienced ICU clinicians and known as a “vent geek.” In fact, one of the reasons why I became a pulmonary and critical care doc stemmed from an early fascination with operating mechanical ventilators.

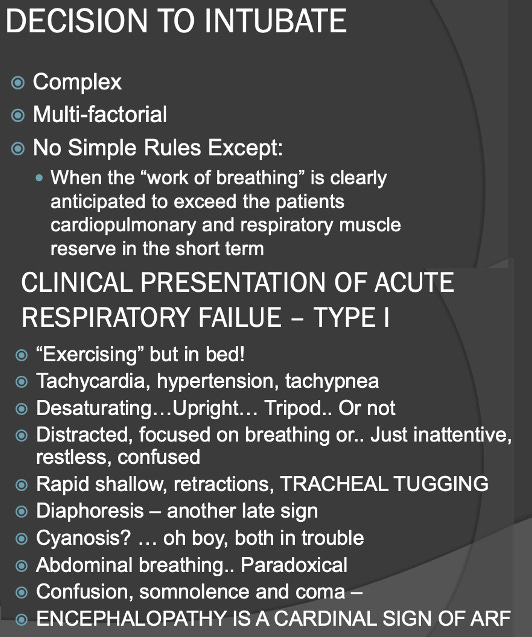

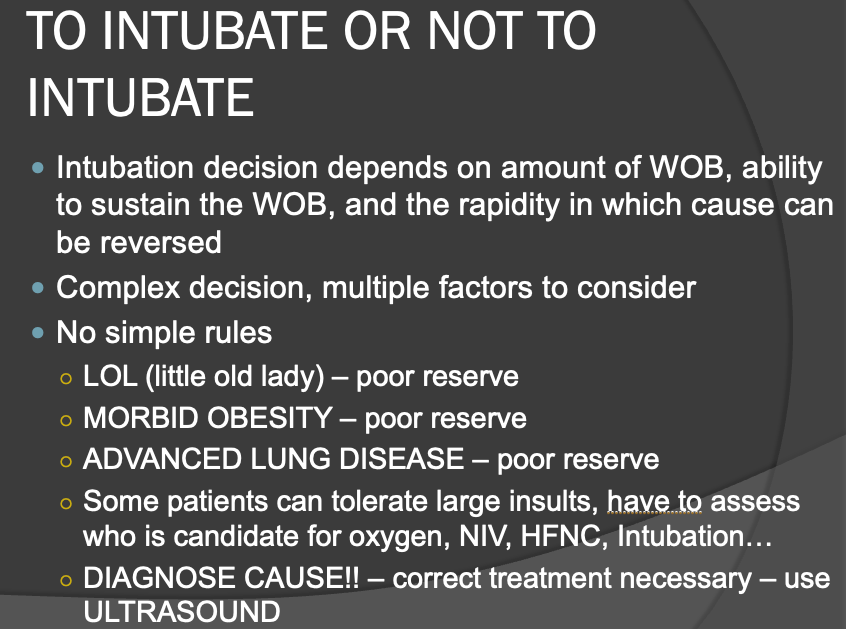

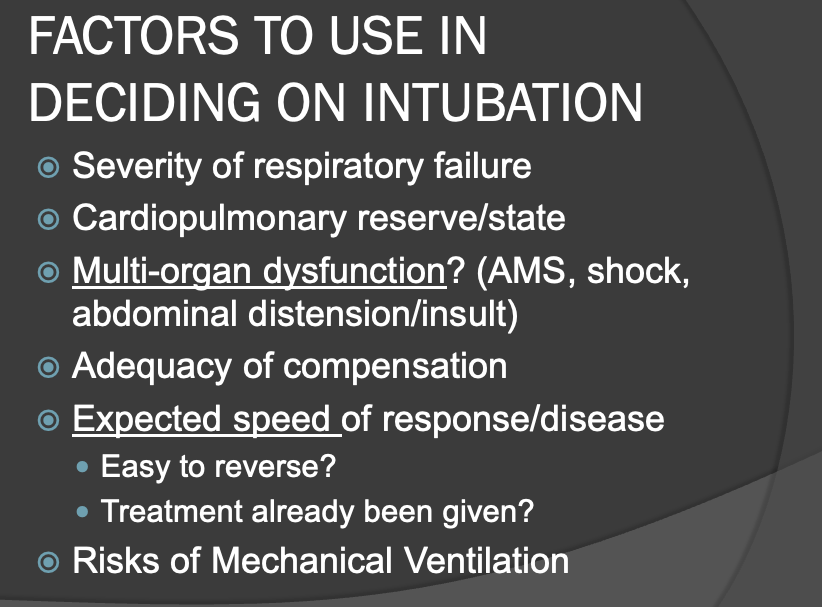

Consequently, I long taught taught the management of acute respiratory failure and mechanical ventilation to medical students, residents, and fellows. One of my core teaching points focused on identifying the optimal timing for the decision to transition a patient to a mechanical ventilator.

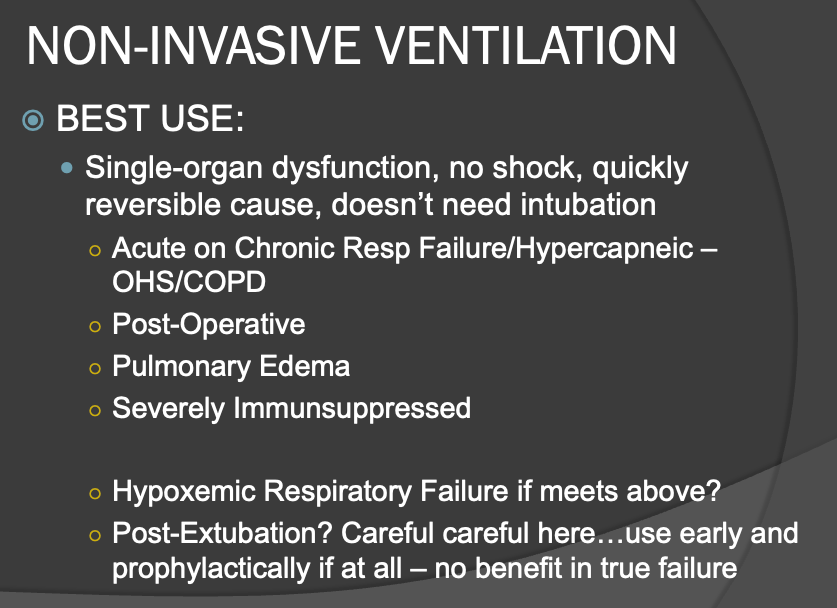

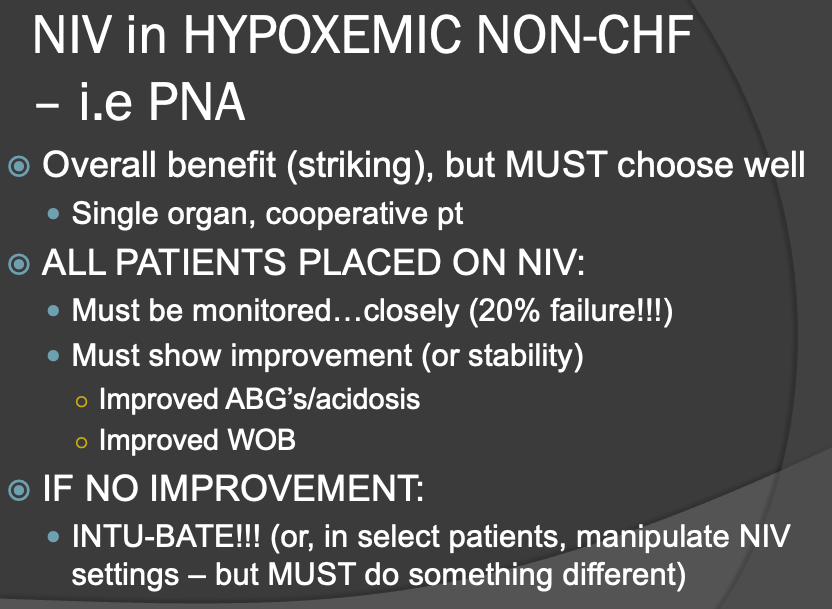

Since I suspect many of my readers are “geeks” like me, I decided to pull some slides from one of my old lectures on acute respiratory failure below. I think they cover all the factors that must be considered succinctly (sorry about all the acronyms, but if you want to decipher them as you go through the slides, they are; ARF: acute respiratory failure, NIV - non-invasive ventilation (BiPAP machines), CHF - congestive heart failure, PNA - pneumonia, HFNC - Heated high flow nasal cannula, WOB - work of breathing, AMS - altered mental status, OHS - obesity hypoventilation syndrome, ABG - arterial blood gas).

From the above, guidance on how to make the decision is simple conceptually but stressfully complex in practice. Basically, the timing of transition to mechanical ventilation is that you always wants to shoot for “not doing it too early” while also “not delaying until too late.” See how simple that is?

The reason for this approach is that mechanical ventilation and ICU care are “double edged swords” in that they can absolutely be life-saving when truly indicated (benefits outweigh risks), but their use typically requires heavy sedation and immobility, two factors that weaken the body’s ability to maintain strength and prolong recovery.

Although it is true that mechanical ventilation, when used inexpertly, can subtly and progressively worsen lung injury, I do not think this was a major factor. Respiratory therapists (who, in my opinion, really “run” the ventilators in most hospitals) generally follow protocols which avoid such harms. And thats an entire other rabbit hole which I won’t go down right now - meaning that although RT’s follow safe protocols, they generally do not have the facility, expertise, or insight to know when a non-protocolized approach is optimal for a patient, something I have tried to teach them my entire career.

Further, all ICU’s aim to remove patients from ventilators as soon as possible because every extra day in the ICU sedated and immobile worsens prognosis and consumes expensive and limited resources. Which is why you want to avoid doing it “too early.”

The worsened prognosis stems less from the mechanically injurious forces of positive pressure ventilation and more from the deleterious effects of prolonged illness when sub-optimally treated. The longer you are critically ill in respiratory failure, the longer you will require sedation and immobility which then can cause confusion, delirium, muscle atrophy, and weakness. All of which prolongs patients recovery and opens them up to developing complications (the shorter time you spend in an ICU the better you will do).

Again, I maintain that it was ineffective and/or absence of treatment which led to prolonged intubation and mechanical ventilation rather than mechanical ventilation itself which caused such high mortality rates. However, the timing of the decision to place a patient on a ventilator is still critically important to me – do it too early and you will be doing it unnecessarily in a proportion of cases while somewhat worsening prognosis, and doing it too late leads to an intubation procedure with higher risks (the act of intubating someone in severe distress with low oxygen is riskier than in a more stable patient). So knowing when to intervene while a patient’s respiratory status is deteriorating is a critical and challenging patient care issue.

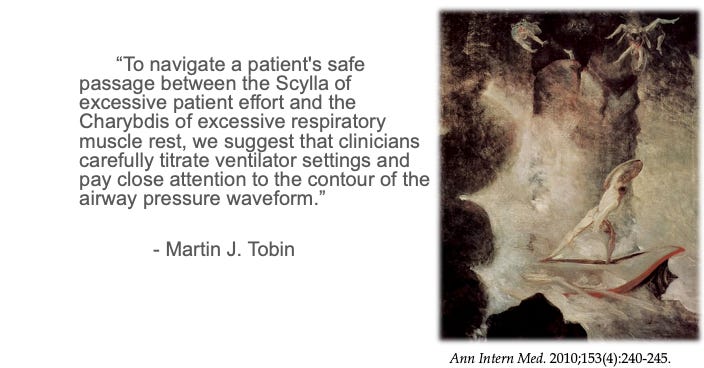

This challenge is best described by Professor Martin J. Tobin whom I call the “Godfather” of mechanical ventilation given that he is the author of the “Bible” of mechanical ventilation, a 3-inch wide textbook called “Principles of Mechanical Ventilation.” It is the only medical textbook that I have read completely… twice (see, I told you I was a vent geek). As an aside, Professor Tobin was the expert witness in the George Floyd criminal case while I was the expert witness in the civil case.

Anyway, in that book, Dr. Tobin invoked the analogy of the mythical Greek sea monsters of Homer called Psylla and Charbybdis when describing the competing factors underlying decisions around mechanical ventilation:

From Wikipedia:

Scylla and Charybdis were mythical sea monsters noted by Homer; Greek mythology sited them on opposite sides of the Strait of Messina between Sicily and Calabria, on the Italian mainland. Scylla was rationalized as a rock shoal (described as a six-headed sea monster) on the Calabrian side of the strait and Charybdis was a whirlpool off the coast of Sicily. They were regarded as maritime hazards located close enough to each other that they posed an inescapable threat to passing sailors; avoiding Charybdis meant passing too close to Scylla and vice versa. According to Homer's account, Odysseus was advised to pass by Scylla and lose only a few sailors, rather than risk the loss of his entire ship in the whirlpool.[3]

Because of such stories, the bad result of having to navigate between the two hazards eventually entered proverbial use.

Tobin invokes Psylla and Charbybdis when he discusses how to “set” the mechanical ventilator properly, but his analogy applies just as well in regards to decisions around the timing of initiating mechanical ventilation.

To wit, here are a couple of slides from one of my lectures on managing mechanical ventilators after intubation (this is slightly off topic from the above, but I thought some of you would find this of interest):

Similarly, knowing when to intubate someone (i.e. the act of sedating and paralyzing someone in order to insert a breathing tube through the vocal cords and into the trachea) is a procedure that presents increased risks the more unstable and distressed the patient becomes. So, you don’t want to do it too early and you don’t want to do it too late.

Meaning that if you don’t establish a supportive airway quickly in severely hypoxemic patients, a cardiac arrest can ensue. Fortunately, due to modern intubating techniques, equipment (video laryngoscopes), simulation training practices, sedation and paralysis protocols, death is rare but still non-zero. Now, although death is quite rare, I have been involved in more stressful/scary intubation scenarios than I (or my patient) would have liked.

“Managing a difficult airway” is the medical emergency of all emergencies because you have a patient still alive where you are responsible to prevent a cardiac arrest from deprivation of oxygen and/or excessive respiratory fatigue. If you are in overall charge in that situation and you fail at the task of successfully inserting the tube, it can result in heavy emotional trauma. Nearly every pulmonary and critical care doc has endured that reality at least once in their career.

Certainly cardiac arrest resuscitations are also emergencies, but the heart is already stopped and CPR is relatively straightforward in my opinion.. so the complexity of decision making is far less in that situation. In one setting you are trying to bring someone back from an arrest while in the other you are trying to prevent its occurrence.

In every instance that I made a decision to put a patient on a ventilator, I would always reflect afterwards as to whether I felt I had done it too early or too late. Psylla or Charybdis. With rare exceptions, I generally felt like I did it too late (not late late, but generally beyond the time that it should have been clear that they were not going to be able to avoid the ventilator.)

The reason for my delaying is that I tried to give every patient as much time and treatment as I could until it was clear they were not improving enough or quickly enough to avoid it. But I tried to give them every possible chance without endangering them. So I would consider myself a “late intubator” by practice. The comfort level with deciding on the appropriate time to intubate obviously varies across physicians as their risk tolerance (and their perceptions of the competing risks) varies according to their training, experience, and personality.

Further, most providers do not perceive mechanical ventilation as harmful. Which is largely true if you just look at the subtle negative impacts of mechanical ventilation in and of itself. But when you figure in the need for ICU care, isolation, sedation, and immobility, the benefit/risk ratio narrows greatly. Again, I remind all that patients with neurological diseases can be supported for decades on mechanical ventilators without progressive harm to the lungs.

I never forget one fellow I had when I was the Director of a Fellowship training Program back in New York who, during his three years of training had more than double the amount of intubations as any other fellow (although not the only reason, I did feel he was an “early intubator” and I tried to guide him to a more conservative approach before he graduated my program).

However, as Covid patients began to be admitted to UW, suddenly a number of my highly trained and experienced colleagues came up to me to argue that we needed a “rule” for when to put a Covid patient on a ventilator.

They were suggesting that we use the amount of oxygen the patient was requiring. I immediately thought this would have innumerable negative consequences but I also understood where they were coming from – the doctors were scared as they had not developed familiarity with the disease and this was compounded by rumors or reports of Covid patients who were supposedly coming in with low oxygen levels and who, despite oxygen supplementation and looking fairly stable, would suddenly “crash.”

This ignorance as to the trajectory of the disease is what triggered the early intubation practices rather than corruption or financial incentives (at least initially in my opinion). Most would eventually (and rapidly) learn that patients with Covid did not “suddenly deteriorate” and instead would do so slowly over time such that decision on the timing to intubate someone was actually much easier that initially feared.

The suggestion to intubate based on oxygen requirements only, although ignorant, was well-intentioned (like many disastrous decisions). I knew these colleagues and knew why they were recommending this. They were concerned about these early patients with Covid and didn’t want to “lose” a patient from inaction. They wanted to protect the “safety” of the patient by avoiding what they thought would be a sudden and perilous intubation procedure (for both the patient and the staff - their was a lot of fear of being exposed to Covid during a chaotic emergent intubation). However, I knew this would paradoxically spell disaster if the practice became standard. Plus, I had serious doubts a viral induced pneumonitis would cause “sudden crashes.”

Another troubling factor which led to “too early” mechanical ventilation was the initial fear of using “heated, humidified high-flow nasal cannulas,” a device which can avoid intubation in certain circumstances (like Covid pulmonary disease). I participated in a number of Covid policy discussions at UW, well before we had admitted our first Covid patient. HFNC’s in my opinion are nothing short of revolutionary in pulmonary and critical care medicine because they can support someone in certain forms of respiratory failure with high oxygen requirements in an incredibly comfortable manner where they can talk, drink, eat, and do not require sedation nor bed immobility (they can sit in chairs/recliners).

Here is where it gets uncomfortable - the reason why leadership at UW avoided using them early on was an exaggerated fear of “contagiousness” to others with their use, i.e. they feared that the high flow rates of oxygen jetting into their noses would “circulate” the virus much more than other devices. I disagreed with this cautiousness, feeling that, even if true, it was not a clinically significant increased risk (more theoretical) compared to the routine risk of exposure when a patient is on a regular nasal cannula or a non-invasive ventilator.

But, it is also true that when patients are intubated and attached to a mechanical ventilator, their risk of infecting others approaches zero. Why? Because they are now breathing through a “closed system.” i.e. the tube in the trachea has a fully inflated ballon or “cuff” such that little to no exhaled air escapes around it into the room, and further, the air that is exhaled back into the tube returns to the ventilator and then passes through a highly sophisticated filter before puffing out the exhalation port on the side of the ventilator and back into the room.

So yes, placing the safety of caregivers atop the needs of patients is a troubling ethical situation, and one that, if it had been true that it truly increased risks to staff, would provide no clear definitive ethical answer because if all the staff got sick, this would prevent the wider population of patients from getting needed care due to lack of staff.

But it was concerns regarding safety of staff which drove the initial cautiousness towards use of HFNC’s, at least at UW.

Anyway, back to my situation that day in March of 2020 when a cohort of colleagues came up to me and proposed that we institute an “oxygen rule” for deciding on when to intubate.

I simply refused to believe that an inflamed lung would lead to precipitous crashes and I knew this both intuitively but I also knew it from talking to my colleagues on the front lines in New York City. So I argued with the “early intubation” crowd that, even though this was a novel disease, it doesn’t change the foundational principal of when to institute mechanical ventilation.

So, at the daily Covid briefing that I led at UW (attended in person or remotely by all residents, hospitalists, and intensivists in charge of taking care of COVID patients), I argued very strongly that we should avoid setting an arbitrary oxygen requirement limit for intubation.

Some had suggested to intubate once a patient required more than 6 liters per minute of oxygen via nasal cannula while others were suggesting something higher. I explained that the indication for the institution of mechanical ventilation should never be based on an oxygen level and instead must be almost solely based on an assessment of the patients “work of breathing” and their ability to sustain that work of breathing.

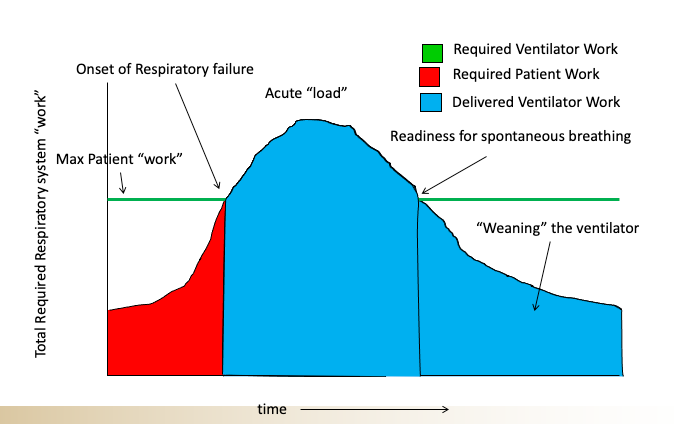

This is where it gets a bit more complicated as a patient’s ability to sustain an elevated work of breathing is itself dependent on multiple factors such as their frailty (or conversely their strength), their mental status, and the cause of their respiratory failure (some conditions are more easily and quickly reversed than others). Here is a schematic that I would use to try to teach this concept to my students (made by my old colleague Nate Sandbo at UW.)

So when you look at a patient who is struggling to breathe you have to ask yourself, can they sustain that amount of effort, for how long, and what is the underlying cause and is it rapidly reversible?

There are certain conditions like acute pulmonary edema which can sometimes be turned around quite quickly with diuretics and blood pressure management and something called a non-invasive ventilator (called BPAP or CPAP machines) such that even when patients are in significant distress, you sometimes have enough time to “turn them around” and can avoid “crashes” (medical emergencies). Other conditions like a worsening pneumonia with low blood pressure from sepsis generally need to be intubated once significant signs of respiratory distress are observed given that in such patients the “turnaround” is not so quick and there is a higher mortality associated.

Anyway, my colleagues and trainees carefully listened and for maybe the first and last time in the pandemic, simply trusted my judgement and advice without too much “argument.” Whew. The idea of setting arbitrary oxygen limits as the trigger for intubation simply disappeared. I’m pretty darn proud of that because I don’t think that was the case around the country and I believe it was one factor which led to the widespread need for additional ICU rooms as well as ventilator shortages.

I must say however, that I do not believe this “early intubation” practice lasted very long as doctors quickly gained more experience in managing Covid patients. They began to recognize that the pulmonary phase of Covid presented as a relatively unique form of respiratory failure in that patients would come in with often quite low blood oxygen levels yet would appear fairly comfortable in terms of their work of breathing, a condition doctors started calling “happy hypoxia.”

Doctors and hospitals also quickly overcame their “fear” of using high flow oxygen devices instead of mechanical ventilation. These devices, called “heated high flow nasal cannulas” (HHFNC) are a marvel of technology as you can deliver incredibly high flows of oxygen (up to 60 liters per minute) into their nose given that the oxygen is 100% humidified and heated (they also helpfully produce mildly positive end expiratory pressure and reduce dead space ventilation).

With normal low flow nasal cannulas that are not fully humidified or heated, if you try to increase the flow past 5 liters per minute, the patients cannot tolerate it due to discomfort and dryness. HHFNC’s thus became the workhorse of Covid and I believe many lives were saved by those devices. Fun fact: the devices were originally developed for use in racehorses (WTF? Horses again?). They were first applied in humans in 1999 then fell into into widespread use after 2010.

However, and I will finish here, there does seem to be a persistent belief among the public that over use of ventilators not only were the proximate cause of death but were done so out of Covid financial incentives. One fact overlooked in the latter argument is that hospital reimbursement rates for mechanical ventilation in any form of acute respiratory failure have always been the highest of any type of patient. That is because the costs of caring for intubated ICU patients have always been astronomical - and early on in Covid, ICU care often entailed weeks of ventilator and ICU support.

Further, the reimbursement rates paid to the hospital has never been a factor in my or my trainees or my colleagues decision to intubate a patient. Ever.

A Hypothetical Case Of Acute Respiratory Failure From Covid

I will finish by sharing a hypothetical case, cobbled from a few Covid cases where I have served as the expert witness. In a few of them, social media mavens “screamed” that the “hospital and the doctors killed him with a ventilator.” Let’s go through a hypothetical case which I believe will best illustrate the factors and decisions in play.

Imagine a 52 year old man presenting to the ER on Day 9 of Covid symptoms, complaining of shortness of breath, with mild to moderately decreased oxygen level. He is placed on a nasal cannula (regular, low-flow one) and kept overnight at a somewhat rural hospital with limited specialist staff. The staff is worried about the lack of specialty care available so they decide to transfer him to a more resourced center (an extremely common occurrence in non-urban ares throughout Covid).

He was tolerating 15 lites of flow via a non-rebreather mask when he departed from the small community hospital on a fixed-wing aircraft to a large University Hospital

En route, he started developing low oxygen levels requiring increased oxygen support.

On arrival to the University Hospital’s emergency department, he was placed on heated high flow nasal cannula at 60 liters per minute, 100% oxygen. However, he then began to “desaturate” to 86% despite the addition of a regular nasal cannula at 6 liters per minute (i.e. he was now on two nasal cannulas).

Although from documentation, his “work of breathing” was not overtly excessive and he was clear mentally, the decision was made to intubate, which was then done in an uncomplicated, controlled, successful manner. They also informed the patient what they were about to do and this was also discussed with the patients surrogate, neither of whom were documented to have objected (I will say that the exact content of the informed consent discussion is rarely documented in regards to the specific risks, benefits, and alternatives communicated).

So, was the decision to intubate the patient at that time wrong?

I would say that there are arguments for both intubating and avoiding intubation at that time but that neither decision would represent a clear violation of accepted medical practice.

Based on my extensive experience managing different forms of respiratory failure and my deep knowledge of the trajectory of pulmonary Covid-19, I personally would have waited. Instead, I would have started treatment in the hope we could “turn him around” before overt distress developed. I would have first trialed him on a non-invasive ventilator (i.e. BiPAP) to see if that would improve his oxygenation and would have kept him under close monitoring in an ICU setting. Further, I would have tolerated what was, to me (not to others) a “mild” degree of hypoxemia - i.e. 86% is not in itself harmful in a generally healthy patient but the trajectory was concerning as well as the amount of support he was on, thus the need for monitoring.

My approach, if not successful, would have led me to having to intubate in a more “high-risk” situation though. The emergency room physician’s decision to intubate at that time led to a smooth, successful uncomplicated intubation.

Thus they avoided having to intubate someone in a state of even lower oxygen reserve (when you intubate, patients are given medications such that they are temporarily paralyzed and stop breathing). This is done to facilitate the insertion of the endotracheal tube through their vocal cords, something that is very difficult or impossible in an awake patient struggling to breathe.

Stopping their breathing when their oxygen levels are even lower than they were at that time likely would have led to an acute, severe oxygen desaturation which can be prolonged unless bag-valve-masking is done quickly and in a skilled manner (which is not always the case). What so few realize is that transient low oxygen levels, even if severe, do not cause brain damage as long as cardiac output/circulation is preserved.

Anyway, the doctors elected to intubate rather than wait for further instability/more severe hypoxemia. They placed more emphasis on stably supporting him with a mechanical ventilator while allowing the treatments to work. I personally would have tried to stably support him without intubating him while also “waiting for treatments to work.” Although my sense is that their decision was “sub-optimal,” it was not unreasonable, not criminal, not influenced by financial incentives, and largely was consistent with the “standard of care” in such situations, both during Covid and prior to Covid.

Further, he was successfully extubated days later.

Thus, my expert opinion, contrary to social media opinions generated from what they knew of the case, instead found that the doctors did not grossly “violate the standard of care” as most doctors (but not FLCCC doctors) would have done the same thing in that situation.

*Writing this Substack is only one of my jobs, and I put a lot of work into it (at the cost of sleep and personal time). I also believe in an ethos of paying people for their work. If you love this Substack and/or get value out of it, consider a paid subscription. Thanks, Pierre

P.P.S - Proud to report that my book is gaining Best Seller status on Amazon in several countries and is climbing up the U.S Amazon rankings… Link:

Is it not conceivable that the same top-down policies that destroyed your and Dr Merick's abilities to treat patients and save lives also lead to hospitals abandoning their patient-first policies to instead depend solely on dictates from on-high out of safety for their actual customers, their shareholders? How many hospitals *still* treat Covid patients with remdesivir? While you were honest, stuck to your guns and would not bow to pressure, why do you believe the rest of the medical industry did not toe the line and just do what they were told fearing the destruction of their careers and thus their ability to help patients from within the broken system? Could your honesty be blinding you?

Dear Dr Kory,

First of all, a thousand "thank you"s to you and your colleagues for all the work done that has clearly saved hundreds of thousands and possibly millions of people who listened to you, FLCCC, and the wonderful protocols that have guided health care professionals as well as lay people trying to navigate a dangerous and previously unknown threat to their lives.

What I wish to convey, is that your wonderfully sophisticated and precise analysis of the ins and outs of respiratory treatment for these patients, as thorough as it is, fails to recognize what most people who work within healthcare find very hard to believe: there are some who intend harm, intentionally and have done so surreptitiously "under the radar" and either used treatments that actively harmed patients, removed treatments or medications that were already helping patients, or withheld treatments that would have helped patients. This is stealth euthanasia and has been revealed to occur within the health care system.

The history of medicine in the US and elsewhere is not without its dark episodes and the past few years is one of the worst. Tuskegee syphilis experiment being just a prominent example of how "Nazi-like" U.S. physicians and public health departments can be. The Euthanasia society of America never stopped trying to influence American health care and some of it went into open, overt promotion of euthanasia and later assisted suicide. The other part went into disguise, covert promotion of undeclared medical killing, unrecorded, with falsified medical and nursing notes of what was done and why.

Perhaps you are not so naive as many. Perhaps it is not easy for a physician to openly speak out about such undeclared stealth euthanasia practices, but with COVID hospital treatment, there were many whistleblowers who indicated they saw how UN-trained nurses and UN-trained doctors were placed in units that were treating COVID patients Untrained nurses managing ventilators who were not accustomed to suctioning patients. Ventilators placed without a respiratory therapist adjusting the volumes, the type and length of hoses, and ventilator MODE settings that are unique for each patient's needs (as you know best, and who nurses like myself know since working with ventilator patients for decades).

There were patients on dialysis, for example, who had UNtrained nurses running dialysis. All these switching of staff where they were untrained was done at the behest of administrators who told those who objected, those who were expert in these areas, to shut up or be terminated. When doctors stood up to administration, they were shut down.

You are right that the proper medication treatments were not used, but there are other methods used to impose death, and there is no other conclusion that makes any logical sense when everything done was 100% in error, 100% of the time. By chance, one can make mistakes. But virtually everything done in the name of helping patients, was in effect harmful to the patients.

Giving Remdesivir known to be toxic and withholding helpful medications (Chloroquine for example) that were clearly known to be helpful (from SARS and MERS decades earlier), and refusing to use medications that were being successfully used in some areas and creating studies using obviously inappropriate dosing to declare these useful medications "dangerous" ... even when they're listed on the W.H.O.'s list of safe and effective medications to be used by all nations ... obviously a nefarious intent was at work, and still is.

We must recognize that stealth euthanasia is practiced widely. The full-length book (in e-book pdf form) explaining all of this is posted online for download at the Healthcare Advocacy and Leadership Organization website at

https://halovoice.org/wp-content/uploads/stealth-euthanasia-1-by-Ron-Panzer.pdf

It is time for the truth to come out and for us to be unafraid to communicate the truth about what we are facing, whether as nurses, doctors, or patients.

Again, a thousand thanks for all you have done to save so many!! May God bless you and help you continue your work!