Chapter 9: The Volcano Alchemist: Asao Shimanishi and the Mineral Code of Life

Using fire, stone, and sulfur, he worked for 20 years trying to coax the Earth to reveal a living liquid mineral complex—one that could purify water, restore soil, and resurrect vitality.

For the mineral minions reading my book, “From Volcanoes to Vitality,” that I am publishing in serial form, today is Chapter 9.

I need to begin this chapter differently than anything I’ve ever written.

If you have followed my work—if you’ve trusted my judgment through these last years—then I’m asking, just this once, for your full attention. No casual reading. No skimming between notifications. I am not dramatizing, and this is not a ploy. Further, I will not do this again. What you’re about to read is, in my honest belief, the most important chapter I have ever written, and possibly the most important thing I will ever write.

Know that I have written hundreds of Substacks before (333 to be exact), and I have never opened any of them like this. I would not risk your trust lightly. All I’m asking for is a few extra minutes of undivided attention—because what follows matters to you, and if you’ll allow me a bit of grandiosity, to the Earth itself. Truly.

So wherever you are—coffee in hand, morning routine unfolding—I ask you to pause with me. There is something here worth your focus.

There are chapters in a life that you don’t plan, and this is one of mine. Not only do I feel today’s chapter is the most significant of this book, but I have come to believe it is the pinnacle of my life’s work.

If I’m being honest, I never meant to write this book. I wasn’t looking for a new crusade, obsession, or scientific frontier (I’ve had enough of those these past five years). I certainly wasn’t trying to become a mineral historian, geochemist, or water purist. Yet something—curiosity, destiny, call it what you like—left me with no real choice. I followed a trail I didn’t lay, and although I didn’t know it at the start, this chapter is where the book began.

If that sounds dramatic, I apologize. I’m not claiming divine inspiration or prophetic purpose—although, in time, I may look back and realize something larger was moving through this work. I am just an earnest physician with a private practice full of the most complex patients on Earth (post–Covid-19 vaccine injured). Since devoting my career to helping them, I’ve been forced to go down innumerable rabbit holes in pursuit of treatments that could ease their suffering.

That is why my practice partner, Scott Marsland, came into my life when and how he did. An astute clinician with a brilliant mind and vaccine-injured himself, he was of the same spirit and goals, and I genuinely believe that ethos has infused our Leading Edge Clinic with the drive and near-excellence it achieves (note I said near).

Over the three and a half years we’ve been in practice together (note I said practice), Scott and I have discovered and integrated innumerable treatment approaches that have mitigated immense suffering. More importantly, that ethos attracted—and retained—some of the best nursing staff in history: empathetic almost to a fault, morally upright, spiritually grounded escapees from the medical system that turned totalitarian during COVID.

If that sounds like marketing, it’s not. It’s me letting my thoughts spill onto the page, because oddly, that part of my life links to this chapter. Now, back to the story.

In my searching journey, I suddenly stumbled onto a mystery. And, as discussed in the Preface, the one trait I will humbly—and reluctantly—admit sets me apart is the ability to recognize people and ideas that are unique, innovative, and impactful. With Themarox and Shimanishi, that vision clicked with a force I had never experienced before. I saw what was hidden in plain sight, and I could not unsee it. Something—someone—wanted this story told.

That “someone” was not me. It was a quiet, almost invisible Japanese scientist named Asao Shimanishi.

To be clear: Shimanishi was not famous, not celebrated, not decorated, and he didn’t want any of the above (nor did I). I feel that my pre-COVID career was similar to his: while I labored endlessly in ICUs, he toiled in labs, mines, and factories. One difference is that he avoided cameras, while I agreed to them—not for exposure, but out of duty. In a global emergency, I felt I had a responsibility as a doctor and professor to share knowledge that could help. I tired of it quickly, but I never said no. Let’s move on—this is not about me.

Despite his achievements, Shimanishi never chased recognition. He did the opposite—he hid from it. While other mineral advocates spent their lives promoting themselves, Shimanishi insisted the miracle was not in him but in the minerals themselves—and in the God who placed them here.

In one of the only and (last) public speeches he ever gave, at the World Water Conference in XXXX, he told an international audience that his mineral complex was “a gift from the Creator” and that he was “working with the angels.” You can imagine how well that went over. That single sentence may explain why so few in academic circles ever took him seriously afterward. His work slipped underground—literally and figuratively.

And yet, his discovery—the world’s first liquid extract of volcanic black mica, dense with bioactive ionic sulfates—quietly began healing soil, water, crops, and ecosystems around the world. Industrial scientists knew it worked. Farmers saw it work. Water-treatment engineers documented it working. But, to date, Medicine has never heard his name.

Which brings us, improbably, to me.

I don’t claim to be a genius or the author of this discovery. I didn’t create it. Like all the other therapies I have advocated throughout my career, it came to me —and then, through me. I feel less like an inventor and more like a conduit—somewhere far downstream of whatever current first carried Shimanishi. Why it flowed to me, and why now, I cannot say. But my role is simple:

I am here to bring Shimanishi out of obscurity and into daylight.

After these months that I have been buried in patents, translated interviews, unpublished lab notes, industrial case studies, agricultural trials, aqueous chemistry reports, and experiments so strange they felt like folklore—I became sure of one thing: his discovery is beyond a modest one. It is historic.

So yes, I hope this chapter is read widely. And if it sounds like I’ve lost it, I’m okay with that. I don’t expect everyone to see what I see. But of everything I have ever written—or will ever write—I believe this work will matter most. Not because I wrote it, but because it comes from the work Shimanish did that the world never saw.

So before we go any further, let me say this plainly:

Despite a century of research into mineral depletion and trace-element physiology, no major scientist, researcher, or author has ever written about Asao Shimanishi’s discovery.

Come with me as we explore his life and work.

Asao Shimanishi

Early Life and Training

Asao Shimanishi was born in Wakayama Prefecture on September 17, 1926. He studied under challenging circumstances during the turbulent pre-war and wartime years, but persevered due to his strong interest in academics. He graduated from the former Wakayama Technical School in 1944, where he learned the fundamentals of technology.

After the war, he went on to the Osaka Institute of Technology, where he deepened his knowledge of chemistry and industrial mining, laying the groundwork for his future career. After graduating in 1949, he began his career in the mining and chemical industries by joining Nippon Tailings Industries (now Sumitomo Metal Mining Co., Ltd.). There, he learned basic mining techniques and gradually deepened his expertise through practical experience.

In 1952, Senju Mining, an unlimited partnership, was established in the Masago mining area of Nakagoto Island, Nagasaki, where he began to develop his own independent business in the mining sector. From that time on, he developed a deep interest in effectively utilizing mineral resources.

The “Tree on the Rock” Moment

One day in his 30s, Shimanishi was meditating on a beach when he opened his eyes and noticed a tree growing out of a remote rock in the middle of the sea—thriving with no visible soil.

It was growing from a crack in a granite boulder, yet without visible soil or water. He figured that the rainwater filling the crack dissolved some of the rock, which then nourished the seedling there.

He became convinced that there was a “vitality” and a “unique energy” in the underlying rock mineral complexes. So, being a highly trained scientist, he decided to investigate by examining the rock and its contents in his lab. He discovered that it was made of rich mineral deposits derived from a specific type of volcanic rock called “black mica” (also known as biotite).

Black Mica vs. White Mica

As he began researching black mica, Shimanishi discovered that it contained vast quantities of rare and exotic trace minerals. To health enthusiasts reading this, black mica is quite different from “white mica,” a popular source of clays such as zeolite or bentonite, which are primarily aluminosilicates with just a handful of minerals.

His investigations revealed that black mica deposits were most prevalent near slow-moving magma, volcanic eruptions, and underwater volcanic vents. That insight led him to recognize that so-called “healing hot springs” are also often located near similar volcanic–rock–fed water.

The Difference Between White and Black Mica

In volcanic eruptions, ash and mineral composition generally fall into two major categories — felsic and mafic — which correspond broadly to the formation of white and black mica, respectively.

Felsic eruptions are silica-rich, viscous, and often explosive, producing lighter-colored rocks such as rhyolite and granite. Their ash plumes appear whitish because they are dominated by silica, aluminum, and alkali elements (like potassium). From these felsic magmas, white mica, also known as muscovite, forms. It appears white because it contains little to no iron. White mica is mainly composed of aluminum-rich aluminosilicates, which are chemically similar to zeolites, known for their high surface area and ion-exchange capacity.

In contrast, mafic eruptions produce iron- and magnesium-rich, lower-viscosity magmas that flow more easily and generate darker volcanic rocks such as basalt and gabbro. Recall this photo from Chapter 1:

From these mafic magmas crystallize black mica, or biotite. Biotite’s darker color comes from its higher iron (Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺) and magnesium (Mg²⁺) content, elements that also play key roles in biological and geochemical systems. These magmas are typically lower in silica but richer in dense, metallic elements, giving rise to the characteristic “black” mica structure.

It is well documented in geological surveys that as iron rich mica rose from the core of the Earth, its magnetic properties allowed it to magnetize and attract other essential trace minerals from the Earth’s surface.

Recognizing a Global Deficiency

Shimanishi believed in a creator and felt intuitively that there was a superior mineral water intended for humanity. In his view, the volcanic material dissolving into the water of nearby mineral springs was what gave them “magical” (my words) properties.

This insight, paired with a prescient awareness, as early as the 1950s, that Earth’s natural trace-mineral deposits were being depleted from its soils and water, harming agriculture and human nutrition. Shimanishi came to believe that the trace minerals produced by volcanic processes were vital to restoring balance in soils, water, and human wellbeing.

Upon this realization, Shimanishi devoted the rest of his life to studying these minerals and, more importantly, to creating a method for dissolving these primordial volcanic minerals in water in a bio-available form—mimicking the natural mineral ionization that occurs in geothermal regions and hot springs (where sulfides from deep Earth often oxidize into sulfates near the surface, such as in Yellowstone). His efforts led to a truly remarkable achievement—historic, in my opinion —when and if this book and its findings become more widely known.

Volcanoes: Earth’s Mineral Source

Geologically, the Earth’s crust is primarily composed of oxygen, silica, aluminum, and iron. All other elements are considered “trace” due to their comparatively tiny concentrations. On average, approximately half a million tons of volcanic ash are deposited into the Earth’s atmosphere each day from volcanoes worldwide.

Shimanishi discovered that the composition of “black mica” mirrored the elemental structure of Earth’s crust itself. Oxygen was dominant (as all minerals existed in oxide form), followed by aluminosilicates, iron, and a spectrum of trace minerals—a near-perfect reflection of the planet’s surface composition. From this, he proposed a radical idea: that oxygen and mineral complexes emitted from volcanoes might have provided the original building blocks of life. Remarkably, like other insights we will explore later, he articulated this decades before the first scientific papers proposing such a volcanic–hydrothermal origin of life were published, in 1981 and 1988, respectively.

Iron & Sulfur – Life’s Building Blocks

A key aspect of living organisms is that both iron and sulfur are required. Hemoglobin in red blood cells has iron at its center; without iron, life is not possible. In plants, iron is necessary for the formation of chlorophyll and serves as a key catalyst in photosynthesis. Sulfates (made of sulfur, of course) play myriad critical roles in supporting life processes, including detoxification, nutrient delivery, metabolism, hormone regulation, and a host of other vital functions.

Shamanishi began to focus on the fact that the most prevalent elements near volcanoes were… iron and sulfur. Recall that the most pervasive rocks near healing hot springs are black mica, sulfates, and micaceous clays. Clays are said to form from weathered micas. Most natural clay minerals are indeed secondary minerals, meaning they form from the chemical weathering of primary silicate minerals — especially micas and feldspars.

Are these springs being “fertilized” by similar, unique mineral deposits?

Echoes of Viktor Schauberger

Remember that Shauberger’s theory was that water existed in two forms: juvenile water created in the atmosphere, and “ennobled” water which formed as water rose through the depths of the Earth’s crust, absorbing rare trace minerals and gaining complex characteristics. One difference between the two men was that Schauberger focused on specific sources of forest spring water, while Shimanishi concentrated on sources of volcanic rock.

Because it was common geological knowledge, Shimanishi likely knew that as iron-rich mica rises from the Earth’s core, its magnetic properties cause it to attract other essential trace minerals. Geological evidence shows that when mica—particularly black mica—contains higher levels of iron, it also tends to harbor a much broader array of trace elements. Iron-rich mineral structures provide flexible binding sites, allowing many rare elements to substitute into the crystal lattice, as below:

In short, where there is more iron in the rock, there is often a richer spectrum of trace minerals alongside it.

The Themarox Breakthrough

I believe that it was Shimanishi’s unique persistence that allowed him to make history—his doggedness was on a scale few possess. It took him almost twenty years of continued study before he succeeded.

In 1977, after 2 decades of trial and error experimentation, Shimanishi successfully extracted a liquid mineral concentrate from black mica—the world’s first of its kind—using a precise balance of heat and sulfur to extract the minerals in a bioavailable, ionic (electrically charged) form.

Eight years later, in 1985, his innovative achievement led to the founding of Shimanishi Kaken Co., marking the beginning of a new era in natural mineral solutions. From that point forward, the mineral complex he developed—later named Themarox® (meaning “rock extract”)—began to move beyond the lab and into practical application across Japan and eventually the world.

What emerged from Shimanishi’s process was a “perfect symphony” of minerals—electrically charged, readily absorbed, allowing for far more than simple nutrition.

During my mineral research journey, one day, the enormity of what he had accomplished struck me like a lightning bolt. I suddenly recognized that Shimanishi’s complex literally represents the “code” for life, akin to the unique mineral composition that spawned the first cellular life forms on Earth 3.5 billion years ago, deep within the ocean near hydrothermal vents. The biochemical mechanisms of how this uniquely balanced ratio of minerals, rich in iron and sulfur, sparked the first cellular life forms on the planet are explained in Chapters 14A through 14E. Good luck.

Even more remarkable was that his mineral complex had additional properties, chief among them the ability to precipitate contaminants and impurities from water, effectively purifying it. Even more incredible was my later learning that he also identified its ability to alter the “structure” of the water into a 4th phase (decades before Pollack was supposedly the first to describe it (see Chapter 13B).

A real-world example of the “vitality” and “life-giving energy” that Shimanishi’s minerals can deliver to water can be evidenced in the following kitchen table experiment:

The photos above show two potatoes at Day 48: the potato on the left was placed in a glass filled with tap water, while the potato on the right was placed in a glass of water treated with Shimanishi’s minerals. As you can see, the potato on the left sits rotting in turbid, brown water, while the potato on the right sits in clear water with a spiderweb of roots, sprouting a tall shoot (the one-foot height is pictured in the upper left).

To me, the above side-by-side image, along with the image that opened this chapter (a tree growing out of a rock), provides a powerful visual suggesting the vitality (life-force) of these primordial minerals.

Ultimately, the story of Shimanishi is that of a patient observer who closely examined the esoteric dance of volcanic forces over the years, which, combined with a unique dedication and persistence, led to the production of a remarkable modern panacea drawn from pre-evolutionary times.

Geologic Serendipity: Two Discoveries, One Soil

There is, in my opinion, a tremendous irony within Shimanishi’s scientific journey. For twenty years, he searched for the most mineral-rich mica—the one pure enough, potent enough, to “cure” the Earth’s deep trace-mineral hunger..

As fate would have it, incredibly, he ended up identifying the most potent mica—the keystone of his process—right there in Japan, hiding in plain sight. The asymmetry of this finding with his countryman, Nobel laureate Satoshi Ōmura, is hard to ignore. Omura had stumbled on the soil bacterium Streptomyces avermitilis—the source of ivermectin—on a golf course an hour’s drive from his lab. The odds of that finding were astronomical, you know why? That single strain has never been discovered anywhere else on Earth. Whoa.

Let’s try to take this in: Omura found an earth-shattering discovery an hour away from where he worked in Japan. And it was the only place in the world where it has ever been found. Meanwhile Shimanishi searched the world as a whole, only to find the best source located an hour???? from where he worked. What?

There’s a pattern in these coincidences: two scientists, two breakthroughs, both pulled from the same volcanic soil—a landscape alive with hidden energy. Japan seems to keep its secrets underground until the right hands come along to reveal them. Maybe that’s what the Earth does everywhere: it waits for us to pay attention.

Also, who nominated me for President of the Fan Club for Geeky (or Lucky?) Famous Japanese Scientists?

Interestingly, as you’ll see in the chapters ahead, Shimanishi’s discovery did far more than provide a rich source of diverse minerals and rare earth elements. When added to water, it infused that water with properties strikingly similar to those described by Viktor Schauberger—yet this time in a form that was reproducible, measurable, and scalable. I thus became convinced that it may be a foundation not only for human and plant vitality, but for the restoration of water itself.

Thus, I consider his achievement both historic and profound—and, remarkably, still unknown. It’s why I wrote this book: because his work hints at something extraordinary—a potential to restore balance and vitality to the living world (particularly the health of humans).

Primordial Substances That Have Shaped My Career

Not that I belong anywhere near the category of these giants, but I discovered something about my career in relation to the above that blew me away.

A month or two ago, while at my desk, deep into the first draft of this book, I was reflecting on Shimanishi’s discovery of “primordial” trace minerals, and I began to think about the two other most transformative substances I have had the pleasure of treating my patients with in my career—ivermectin in Covid (and cancer) and the use of low-dose, sublingual, daily ketamine in the treatment of neurological diseases (my Substack series on ketamine follows this book, and I believe it will be similarly transformative).

Ivermectin

Remember that ivermectin is produced by Streptomyces avermectin, the bacterium that Omura isolated from the golf course soil sample. On a whim (or an intuition), I asked AI, “How old is that bacteria?” Answer:

Streptomyces species are ancient bacteria. Phylogenetic and genomic studies suggest that the genus diverged from other actinobacteria roughly 400 to 450 million years ago—around the time plants first began colonizing land.

What? Ivermectin was one of the first forms of life created by Shimanishi’s life-sparking minerals? I was literally starting to tremble when I then asked, “What about ketamine? How old is that?

Ketamine

Before we get to the answer, know that I only asked that question because I had only recently learned that ketamine can be sourced from nature. If any of you were to read about ketamine from a textbook, you would learn that it was initially synthesized by modifying PCP (yes, PCP) in a lab in the 1960s. But get this: one of my ketamine mentors, psychiatrist Michell Liester of Colorado, had sent me a paper just a few months ago, published in 2020, in which Brazilian researchers reported discovering a “natural” source of ketamine —specifically a fungus known as Pochonia chlamydosporia.

Thus, my question to AI was “How old is the fungus Pochonia chlamydosporia?”

…this lineage emerged during the diversification of terrestrial fungi, which is believed to have occurred hundreds of millions of years ago, likely in parallel with (or shortly after) the colonization of land by plants during the Devonian and Carboniferous periods, about 360–400 million years ago. Fungi in the order Hypocreales, to which Pochonia belongs, are considered an ancient lineage that radiated as land plants and soils developed.

Wait, what? The origin of the three most remarkable substances I’ve used in my career - a fungus, a bacterium, and a rock - all arose from or contributed to the beginning of life itself? Are all of them “primordial” therapies? Did I invent a new class of therapeutics?

I immediately tried to have some fun with this idea of a new “class” of therapeutics which would, of course, be named after me (recall this previous humorous post about my desire for my name to be part of a medical eponym). I started with “Kory Minerals,” but it was so dull and unoriginal that I got embarrassed. So I asked AI for help. Check out its suggestions, please vote (I like the first one best):

Kory’s Geological-Pharmaceutical Complex

Kory’s Primordial Soup Set

Korygenics™

Primordia Koryana (not bad!)

If you find the parallels between Ōmura and Shimanishi as mind-blowing as I do, now consider this: they made their discoveries within just a few years of each other—1973 and 1977—and within only a few miles, both working in the quiet suburbs of Tokyo. What on Earth—or above it—was happening there at that time? The gods of soil and stone must’ve been busy over Japan in the seventies.

I want to make the egotistical argument that my birth year of 1970 is also somehow connected to the above, but I don’t want to push it :). Ok fine, so it’s just a coincidence. Or maybe that same current of mineral mischief pulled me, as a baby, into its flow.

Shimanishi’s Vision Realized

Again reflecting on Shimanishi and his life’s work, I am struck by how far ahead of his time he was. Decades ago, he had already identified the problem of trace mineral depletion in soils and water and believed that a time would come when humanity would be in dire need of a solution. He saw the answer within black mica and set out to create what he called the “superior solution.” When he finally perfected his process, he stated, “This was the water the Creator intended for humanity to have.”

True to his word, the mineral complex released from black mica contained up to 80 ionic trace minerals in an unadulterated primordial form—literally drawn from the rock that contains the minerals that served as the building blocks of life.

Even more momentous, his method of extracting the trace minerals from the rock imparted them with an electrical charge. As importantly, his use of sulfuric acid converted each mineral into a sulfated form, thereby creating a water-soluble salt complex. His process made the minerals highly water-soluble, easier to disperse, and more readily transported in water—mimicking the way trace elements naturally occur in hot springs and geothermal waters.

A Natural Wonder

After all those years, Shimanishi’s immense, prolonged effort produced a crystalline liquid derived from black mica’s silicate cage—again, a “perfect symphony” of living, ionic minerals, released when mixed with water.

Even more striking is that the naturally occurring ferric iron and aluminium sulfated compounds in this liquid have been shown to neutralize or reduce suspended contaminants, thereby improving water quality. The purification process occurs in four stages—flocculation, agglutination, coagulation, and deposition—where charged minerals attract and bind dissolved contaminants and pollutants, causing the clusters to grow larger and heavier and then settle to the bottom, leaving the water visibly clearer.

What’s impressive is that this mineral complex belongs to nature alone; no man-made process can synthesize a composition of minerals like these. By adding these minerals to water, Shimanishi’s process recreates the kind of mineral-rich environment found in some of the world’s most revered hot springs, which are likewise rich in sulfates.

Now, as an illustration of these “purifying” properties, check out the below 3.5-minute clip from a famous Japanese news broadcast of a “clean-up” event where his minerals were used to clarify a brackish, polluted pond at a famous Shinto shrine in Tokyo (in just 4 hours). Fun fact: the shrine and pond are especially popular with Japanese students who visit to pray for success in entrance exams and studies.

At the 2:00 mark, you’ll catch a rare public sighting of Shimanishi, smiling as he drinks the freshly treated pond water from a glass mug that they had lowered into the pond on a rope:

Also super cool is this clip from a Japanese news program, which followed the segment above. Check out how the newscaster purifies a fish bowl live on TV, only 1 minute long:

AUTHORS NOTE:

Before we end, there is one more thing I need to say—something I have never written publicly until this moment, and I ask you to receive it in the same spirit in which it is given.

After months of studying Shimanishi’s minerals, experimenting with them, reviewing decades of hidden research, speaking with engineers and agronomists from Japan and beyond, and seeing with my own eyes what they could do to water, soil, fish, crops, and living systems…I realized something uncomfortable: it wasn’t enough to write about this. If Shimanishi’s work was real—if his “superior water” truly represented a missing foundation in human and ecological health—then telling the story without building a pathway for people to access it felt like unfinished work. It felt like cowardice.

Similarly convinced, I decided to form a small company, like Shimanishi, with my wife Lisa and my practice partner Scott Marsland to distribute the ionic, sulfated mineral complex that Shimanishi discovered. I did not set out to become a businessman. I did not dream of launching a product. And I certainly did not imagine announcing this in a book. Yet here we are. We named it “Aurmina,” meaning “golden,” “mineral,” “essence.”

Let me be painfully clear: this is not yet a supplement (the amount of minerals needed for water purification is too low to reverse deficiencies in most), not yet a therapy, not yet a miracle cure, nor medical advice. In its current form, it is only a water-purification, mineral-balancing, and water-structuring complex—nothing more. The future formulations for agriculture, animals, and humans will be developed separately, rigorously tested, and stewarded with transparency.

Yes, I hope this product succeeds. But what surprised even me is that soon after the initial dreams of financial success incentivized me, profit stopped being the point. If this works—if it genuinely offers what Shimanishi believed it could—then there are nursing homes, orphanages, farms, villages, and families around the world who will never be able to afford it. And that is where I intend the heart of this mission to live. If there is abundance, it will be used to fund research, support non-profit efforts, and place this “golden elixir” into the hands of those who need it most (for more on the Golden Elixir, see Appendix C).

In my mind, I started thinking of Robin Hood, but different —way different. My dream became simple: let those who can afford to pay, pay—so those who cannot, don’t have to. Either way, both reap benefits.

I just wanted to let you know that I am not asking you to buy anything. I am asking you to understand why I could no longer keep this discovery on a bookshelf. Shimanishi spent a lifetime pulling life from stone. The least I can do is help make it visible. And if this chapter has earned anything—your trust, your attention, your curiosity—then let it be used for something larger than all of us.

Onward—with humility and hope, guided by a physician’s caution—and by the sense that the Earth hides its gifts until we’re ready to steward them.

Next: Chapter 10 - The Mineral Water Hypothesis: The Science and Stories of Healing Springs

P.S. If you want to learn more about the water purifier we made from Shimanishi’s volcanic-mineral complex, go to Aurmina.com.

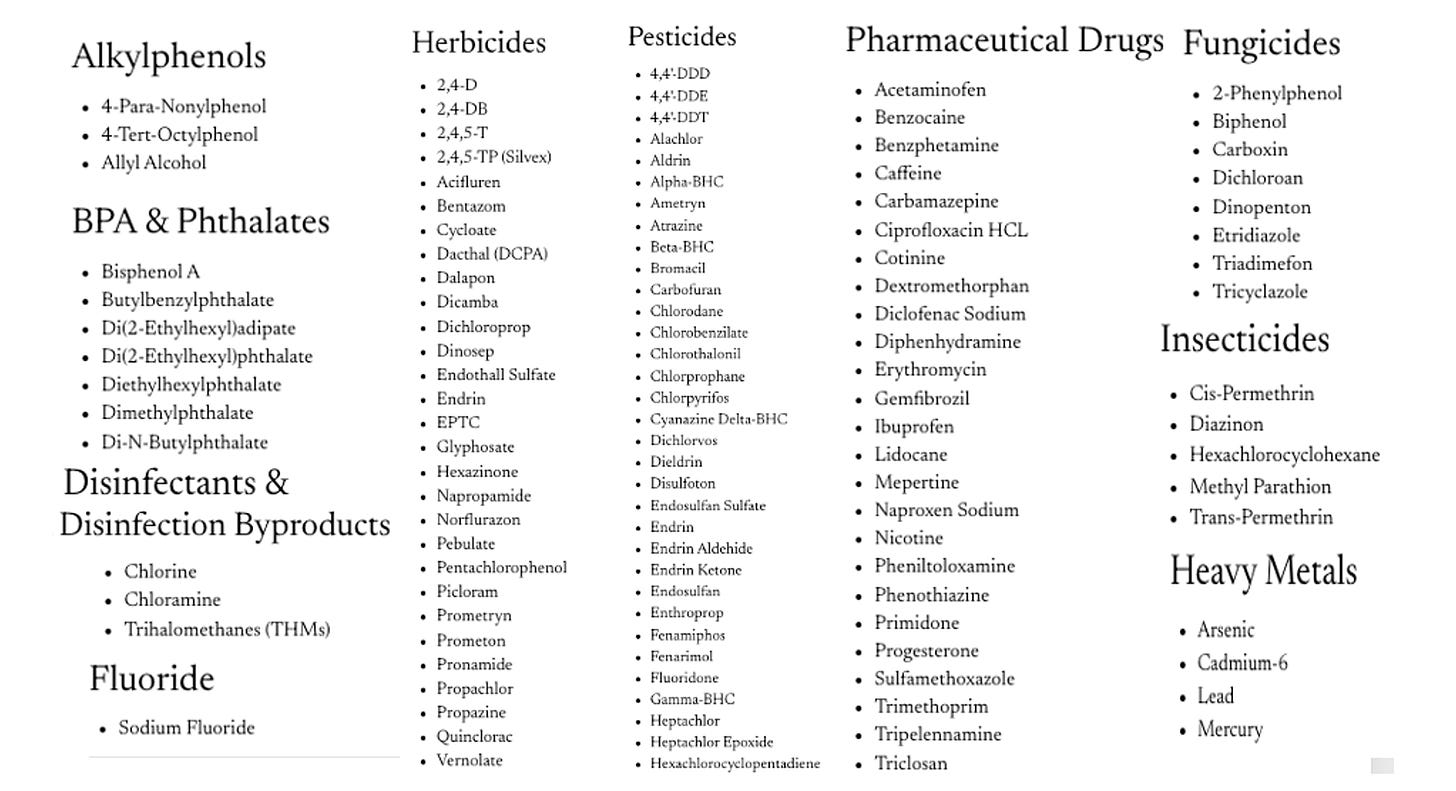

P.P.S. — If you’ve read Chapter 19, “What’s Really in Your Water,” you already know how critical purification and remineralization are in an industrial world. As awkward as it feels for me, I will be manning a vendors table with Lisa at the CHD conference tomorrow, where I’m speaking. We printed a list of 250+ contaminants Aurmina removes—all backed by extensive testing. The list of contaminants and toxins that it removes is a sight to behold. See below. And for the graphene-oxide crowd… yes, it removes that too.

Upcoming Book Publications

Yup — not one, but two books are dropping from yours truly (at the same time? What?)

If, instead of (or in addition to) this Substack version, you prefer the feel of a real book—or the smell of paper—or like to give holiday gifts, pre-order From Volcanoes to Vitality, my grand mineral saga, shipping before Christmas.

And if you want to read (or gift) another chronicle of suppression, science, and survival, grab The War on Chlorine Dioxide—the sequel you didn’t see coming—shipping mid-January. On this one, I say: “Buy it before they ban it.” Hah!

© 2025 Pierre Kory. All rights reserved.

This chapter is original material and protected under international copyright law. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical

It’s great to get first dibs on the book info and the Aurmina!

Honestly, I’m just glad I can support your work and help you in a small way to learn more so you can share and keep helping others. I know that’s your goal.👍🏼

I had to buy this product just to conduct my own experiments. I’ll let you know how it goes!