Chapter 3 - The Dying Ground: How Modern Agriculture Is Unmineralizing the Earth—and Ourselves

As we stripped the soil of its minerals, we unwittingly stripped vitality from our crops, our livestock, and the human body itself.

Mineral Month, Day #3: Good morning, my mineral minions, just bear with me, but I am still trying out my potential monikers for the month. I initially went with “Mineral Man,” moved to “The Mineral Maestro,” skipped “Mineral Moron,” and, for today, landed with “The Mineral Whisperer.”

Why This Is A Problem: Yesterday, I started a tradition of asking AI, before launching that day’s chapter, “What are the dumbest nicknames for the author?”

Out of the choices I got today, I chose “The Mineral Whisperer,” and that man is ecstatic. It will be my preferred identity for today—and just for today—it may —and almost definitely will —change by tomorrow.

My “mineral minions” are arriving in droves, my book is on fire, and “Mineral Month”, initially intended as a humorous (and feeble) promotional exercise, has become a real thing (who woulda thought?). I am beyond ecstatic. You guys are getting it so quickly!

Bobby and my MAHA friends, we haven’t talked in a while, but the minerals are coming —and coming strong. My non-profit, “Rebuild Medicine,” is reaching out for help with a systemic “mineral resurrection” across soils, water, livestock, and humans. I know, I know, it sounds very grand, but read the book and let’s talk.

CHAPTER 3

Problem: Soil is our natural source of more than 98% of human nutrition (and minerals). As land dwellers, our primary connection to minerals is through a diet of plants that extract and assimilate minerals from the soil as they grow, and secondarily through the meat of animals that eat plants. Minerals are essential for our well-being, yet they have long been taken for granted—overshadowed, in my view, by an obsessive focus on over-supplementing vitamins while only a small minority (to put it mildly) have given them the attention they deserve.

Again from Heinrich:

“Earth is a terrestrial planet, a solid sphere of rock with a metallic core. In the beginning, the terrain was all scalding rock, unbearable heat, and choking fumes. Since then, its surface has cooled, continents have drifted, mountains have risen and eroded, and life has emerged benign and green. Nearly all visible traces of the early planet have been wiped away. Plant and marine life emerged before land life evolved, and scientists believe that all land life in the beginning was vegetarian.There were at least eighty-four minerals (Ed: underestimate) everywhere near the earth’s surface, so plants from then were likely highly nutritious.”

Many geological models propose that, over what are believed to be millions of years, the Earth’s surface has been shaped by wind and rain erosion, along with the steady influence of continuous plant growth.

Yet one of the central tenets of this book is that, more recently— and more worryingly—modern farming practices over the past century, particularly the use of chemical fertilizers, have massively and precipitously depleted Earth’s surface minerals.

Now it is like a plague. The top three feet of soil (across the world, mind you), where our plants grow, is severely depleted of minerals compared to what they were a hundred years ago. When you test earth or volcanic ash from deep zones, you find anywhere from 60 to more than 100 minerals. But we don’t know what we don’t know. The majority of standard surface soil tests today, from anywhere in the world, assess no more than 20 minerals in our soils.

This mineral-poor soil, as you will learn, has serious repercussions on our well-being, and that is because, again, the mineral content of our plants and meat is directly related to that of the soil.

The Contribution Of Modern Agricultural Practices

Fertilizers and the Soil’s Natural Balance

Chemical fertilizers disrupt the mineral and microbial balance in healthy soil. By killing beneficial microorganisms, they fail to provide the full range of natural minerals plants need. This creates nutrient imbalances, where an excess of one nutrient blocks plants' ability to absorb others, resulting in lower food nutritional value as bulk crop production rises.

More Food, Less Nutrition

Crop yields and per-capita food availability have steadily increased thanks to intensive farming methods, artificial fertilization, pesticides, irrigation, high-yielding varieties, and other environmental techniques. At the same time, malnutrition has continued to rise because soil life is disrupted, and the nutritional density and quality of food crops have declined. Today, people are overfed (you don’t say) but still undernourished because they consume nutrient-poor diets.

The Ripple Effect on Livestock

Modern cattle now require supplements because decades of intensive agriculture, widespread fertilizer use, and erosion have depleted key minerals—such as copper, selenium, zinc, manganese, cobalt, and iodine (these are just the ones we track)—from soils. Forage crops are less nutritious than they were in the past.

Changes in livestock feeding (monocultures, processed feeds) and increased production demands mean their mineral needs are greater and no longer naturally met. This leads to health problems unless adequately supplemented. Antagonistic substances in modern soils can further block the absorption of needed minerals.

A Vicious Chemical Cycle

Each year, billions of pounds of pesticides, herbicides, and other toxic chemicals are applied to crops and released into the air, aggravating soil depletion, contaminating the food supply, and leaching into our freshwater supplies (see Chapter 19 for a “deep” dive into the issues with our water supply).

The shift to high-yield, disease-resistant crop varieties has also contributed to lower nutrient levels in food. Exhaustion of soil accelerated after 1900 and has continued to grow exponentially since the advent of the “green revolution.” This dynamic creates a vicious cycle: the widespread use of pesticides and insecticides increases further because crops have become more vulnerable due to mineral-deficient soils.

Significant research has found that only plants with sufficient mineral intake from the soil can robustly defend themselves against invading pathogens.

At the risk of foreshadowing, later I will provide evidence that plants fed a diversely mineralized diet not only thrive to the likes of which you have never seen, but also don’t require (or don’t require as many) toxic chemicals to keep the pests away.

Fifty years ago, healthy plants rarely needed such fortification; their natural vigor repelled insects. This basic fact—like many basic facts ignored in my own field, the bio-medical pharmaceutical industry—has launched the agricultural sector into a similar world of mind-boggling dysfunction.

Nutritional Dilution: The Numbers

As a result of the above changes in agricultural practices, numerous studies indicate that, starting in the mid-1800s, trace minerals began to be depleted from our soils. The table below plots the declines in countless major and trace minerals between 1850 and 1955:

The above shows the declines until 1955. However, 70–80 years ago, the nutritional dilution rate was approximately 20%, whereas over the last 30–40 years, it has reached 80%. Studies from many countries find that the nutrient density of fruits, vegetables, and other food crops has declined precipitously.

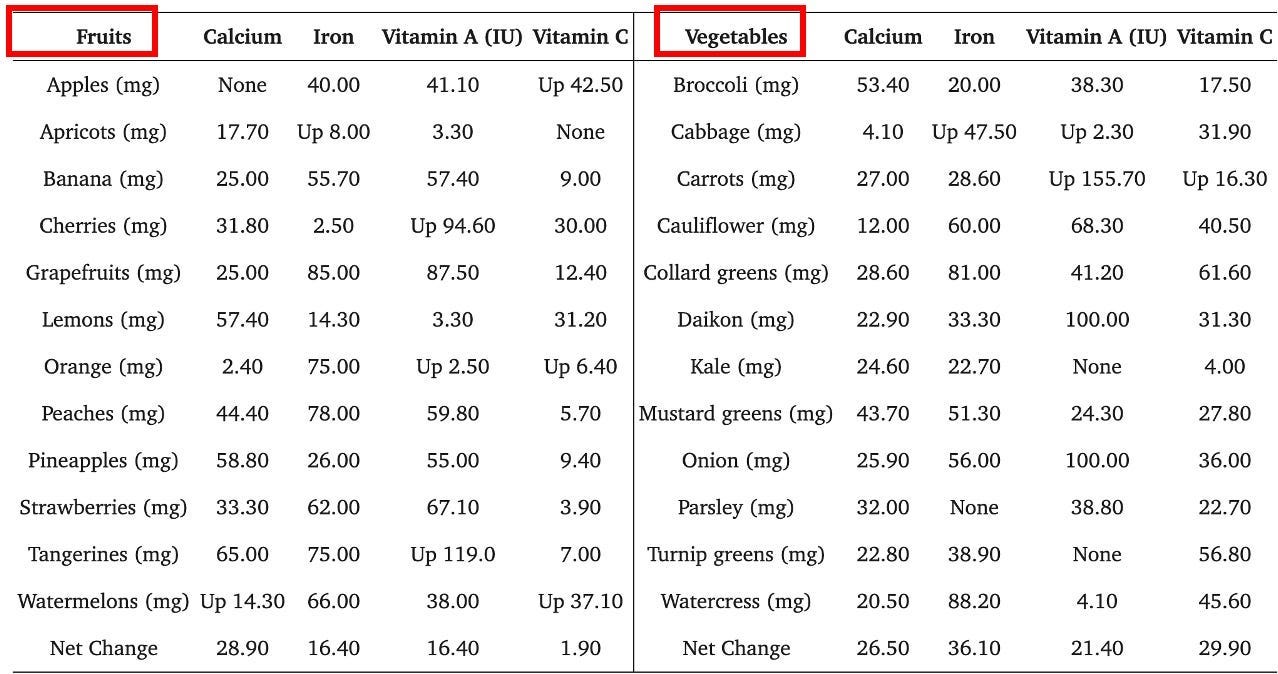

In the table below, check out the plummeting mineral and vitamin content, in just the 20-year period from 1975 to 1997.

(All figures represent % decreases unless indicated by “up”)

Although only the fates of two vitamins and two minerals are given as examples in the table above, this 2024 paper, entitled “An Alarming Decline in the Nutritional Quality of Foods: The Biggest Challenge For Future Generation’s Health,” shows that all trace and ultra-trace minerals are declining similarly.

Even more important than the numbers is the fact that, historically and continuing up to the present day, modern agricultural sciences do not—I repeat, do not—in any way, shape, or form, measure and track levels of minerals that are outside what I will later define for you as “the Big 14.” To the present day, research into what should be considered “essential” and “non-essential” minerals remains shockingly thin (and prematurely terminated historically for reasons you will learn later).

I have been saying that you’ve probably never heard of many of these minerals. For example, do you know what happens if you are starved of antimony, strontium, europium, germanium, vanadium, lanthanum, etc? Nobody really does, actually, so how do we know they are not “essential,” or more importantly, like boron, “beneficial?” You will not like the answer, I promise. But let’s start with what we do know.

Major Minerals

Definition: Needed in larger amounts, >100mg/day; concentration above 0.01% of body weight.

The seven major minerals needed by the body are calcium, magnesium, potassium, phosphorus, sulfur, sodium, and chloride.

Magnesium: Supports muscle and nerve function, strengthens bone structure, and powers energy production. Deficiency triggers muscle cramps and arrhythmias.

Potassium: Regulates fluid balance, nerve signals, and muscle contractions. Vital for heart health and prevents hypertension.

Calcium: Builds and maintains bones and teeth, supports nerve signaling, and drives muscle contraction. Prevents osteoporosis and rickets.

Sodium: Maintains fluid balance, nerve function, and muscle contractions. Excess intake raises blood pressure.

Chloride: Acts as a major electrolyte alongside sodium and potassium, maintains fluid and electrolyte balance, forms hydrochloric acid in the stomach for digestion, and supports kidney function in regulating blood pH.

Phosphorus: Forms bones and teeth, powers all cells via ATP, supports DNA/RNA formation, and regulates acid-base balance.

Sulfur: strengthens tissues, skin, hair, nails, bones, and teeth; supports amino acid synthesis, detoxification, and insulin production; aids healing, oxygen use, and skin health.

Minor Minerals

Also called “trace” minerals, they play vital roles, but the body needs only small amounts—typically less than 100 mg per day.

Like the major minerals, there are 7 “essential”, “trace” minerals:

Iron: Carries oxygen in blood for energy and immunity; deficiency causes anemia, fatigue, hair loss.

Zinc: Powers enzymes, immunity, skin, growth, fertility; deficiency impairs repair, skin, and immunity.

Copper: Powers enzymes, iron absorption, immunity, skin, and tissue health; deficiency causes anemia, joint pain, weak immunity, poor growth.

Manganese: Builds bone/cartilage, aids metabolism, bolsters antioxidant defenses; deficiency affects growth, bones, and joints.

Iodine: Needed for thyroid hormones and metabolism; deficiency causes goiter, metabolic disorders, hypothyroidism.

Selenium: Acts as an antioxidant, protects cells and immunity,, supports reproduction and skin health; deficiency causes aging, arteriosclerosis.

Molybdenum: Powers metabolism/detox enzymes; deficiency raises cancer/stomach risks.

Now, let’s do some “mineral math.” Although the exact number is not known, Earth is thought to host more than 115 minerals in its soils. About 94 of these occur naturally in different parts of the world or in volcanic ash (again, I’ll discuss the importance of volcanic rock sources later).

So, if there are up to 94 minerals in the soil, and only 7 are of “major” importance, while another 7 are of “essential” importance in trace amounts, that leaves 80 other minerals potentially present and absorbable in the foods we eat.

Enter the “The Kory Classification Schema For Minerals,” where I divide these 80 remaining, “non-essential” minerals into two categories, which I will call: 1) ultratrace and 2) rare-earth elements (REEs). I refuse to defend that schema further, despite it being a little confusing and contradictory (i.e., because some “essential” minerals above are needed only in “ultra-trace” amounts, but if you get over it, we can move on).

Historical Gatekeeping: How “Essential” Was Decided

In terms of a historical timeline, the first list of essential minerals was in the textbook called The Newer Knowledge of Nutrition by Elmer V. McCollum in 1918. Next, the League of Nations published the first official international standards list in 1936, and the first U.S. Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) list came out in 1941, explicitly listing certain key minerals.

However, the foundational effort that first determined “essential” mineral requirements is considered to be the 1974 FAO/WHO handbook, which later culminated in the landmark 1998 FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Human Vitamin and Mineral Requirements. This latter document has remained “the Bible” for codifying global recommendations on essential minerals.

So how was a mineral determined to be “essential”? Scientific and regulatory bodies (the World Health Organization, the Institute of Medicine, and nutrition societies) have historically required that a mineral demonstrate a demonstrated, irreplaceable biochemical function in humans, with clear deficiency symptoms and evidence that supplementation restores health. This list was built from observable links between the absence of a mineral, the presence of disease, and recovery with supplementation —relying mainly on long-term population health studies and animal models.

That means determining which minerals were “essential” required identifying their absence and linking it to a disease. Yet, we couldn’t even accurately identify the presence or absence of most ultra-trace minerals and REEs until the 1980s, after the advent of ICP-MS, which enabled ultra-sensitive, multi-element analysis in biological samples, revealing dozens of additional trace elements at low concentrations.

Problem—in the case of dozens of trace minerals and REE's, at the time of the 1998 FAO/WHO Mineral Requirement document, scientists had only been able to accurately measure them less than ten years prior, an absurdly fleeting amount of “scientific” time to understand their importance. Thus, it is clear that the scientific establishment had already decided they were of little importance—after all, they exist only in “trace” amounts, so how important can they be?

The Fallibility of Mineral Classification

Illustrating a point I made above, and which will have import later, some of the minerals on the “essential” list (selenium and molybdenum), were initially considered to be “toxic” until they were later discovered to be essential as follows:

Selenium (Se):

For decades after its discovery in 1817, selenium was considered only a poison. It caused hair loss, nail changes, and “alkali disease” in livestock. It wasn’t until the 1950s–60s that scientists identified selenium as a component of glutathione peroxidase, an antioxidant enzyme. This discovery transformed selenium from a “toxin” to an essential trace element.Molybdenum (Mo):

Long regarded as a contaminant metal until the 1950s, when it was shown to be a required cofactor for xanthine oxidase and sulfite oxidase. Today, it’s recognized as essential in humans, with defined deficiency syndromes.Fluoride (F):

Although not technically considered “essential,” I do want to point out that it was initially dismissed as a harmful contaminant in drinking water, but later recognized as beneficial at low concentrations for strengthening enamel and preventing dental caries. So, in 1962, the USPHS (the forerunner of the CDC) began recommending that it be added to our drinking water. More recently, my MAHA brothers and sisters have been “inconveniently” pointing out that studies have found that it lowers children’s IQ! Know that 2 out of 3 Americans drink fluoridated water. The CDC states: “State and local governments decide whether to implement water fluoridation. Often, voters themselves make the decision.” Wild.

Ultra-trace Minerals (i.e. non-essential)

What will follow is a long list of ultra-trace minerals and their physiologic functions in the human body. The evidence supporting the functions described below comes from this WHO report, the U.S. Research Council report from 1989 titled Diet and Health: Implications for Reducing Chronic Disease Risk, and the book “The Untold Truth” by Elmer Heinrich.

The problem with the latter reference is that, although Heinrich made many accurate statements summarizing the importance and functions of many of the minerals addressed in his book, I could find no support for several statements about certain ultra-trace minerals in the medical literature (especially the rare-earth elements). That is because, unhelpfully, he did not provide citations for them.

Still, I was intrigued by the fact that he “claimed” that the rare-earth elements (REE) neodymium, praseodymium, germanium, and europium all “doubled life span in lab animals.” At the risk of making his claim seem compelling to human physiology, know that it is not uncommon for REEs to have physiologic importance in animals or plants and none in humans, so don’t go buying REE supplements just yet.

Ultra-trace Minerals

For efficiency, scroll quickly past— the list is dizzying—but while you do, notice how these “ultra-trace” minerals have been found to support myriad biochemical, metabolic, enzymatic, and organ functions.

Antimony: Aids immune and joint conditions; may help arthritis and bronchitis; possible anti-inflammatory role.

Barium: Acts as a biocatalyst; may regulate blood pressure; role in hypertension treatment unclear.

Boron: Key for bones, joints, estrogen regulation; aids mineral absorption and activates vitamin D; deficiency may cause osteoporosis and mental decline.

Chromium: Essential for sugar metabolism; regulates blood sugar; deficiency raises diabetes risk and weakness.

Cobalt: Forms part of vitamin B12; supports red blood cells and nerves; deficiency impairs cell division and hemoglobin synthesis.

Fluorine (Fluoride): Strengthens teeth/bones, prevents cavities; deficiency causes decay and weak bones (excess causes lowered IQ?).

Gallium: Little data; used for TB treatment.

Germanium: Supports immune system, detox, wound healing; potential anti-aging and anticancer effects.

Gold: Boosts cell activity, fights infection, acts as an antioxidant, supports heart/lungs, heals wounds.

Lithium: Supports mood and brain function; mental health stabilization; non-plant forms toxic.

Nickel: may play a role in urea metabolism and hormonal regulation.

Osmium: May help nervous system; limited data.

Platinum: Breaks down oxygen-rich fluids; effects unclear.

Radium: Rare earth mineral; no known human role.

Rubidium: Present in blood; used experimentally for muscle pain/MS; aids cell transport.

Silicon: Builds connective tissues, bones, skin, nails; helps heal and hydrate.

Silver: Antiviral, antibacterial, fever reducer; acts as antiseptic.

Strontium: Supports bone density/strength, dental health, pain reduction; may prevent osteoporosis..

Vanadium: Aids sugar/lipid metabolism, bone, fertility; deficiency causes bone/cartilage defects (in animals).

Another issue I had with Heinrich is that he ascribed physiologic functions to some ultra-trace minerals that have none in humans—ones like aluminum, lead, and arsenic —suggesting he was conflating (or at least not distinguishing) minerals that have proven physiologic functions in animals and not (yet?) in humans.

Rare Earth Elements

So if selenium, molybdenum, and fluoride were once dismissed as inert or toxic before their physiologic roles were revealed, I maintain that rare-earth elements may also one day be found to have subtle or conditional roles in human biology (but only if such research gets funded and designed, because it hasn’t happened yet).

In the list of the ultra-trace minerals I presented above, only about 19 were included, thus, we have covered only 31 so far. So, now I will introduce you to the ones I guarantee you have never heard of, which are called “rare earth elements (REEs).” These refer primarily to the “lanthanide” series, along with additional elements which I will leave off mentioning for now:

Lanthanides:

Lanthanum (La): Rare earth mineral, poorly studied; some researchers have used it for eye hypertension.

Cerium (Ce)

Praseodymium (Pr)

Neodymium (Nd)

Promethium (Pm)

Samarium (Sm)

Europium (Eu)

Gadolinium (Gd)

Terbium (Tb)

Dysprosium (Dy)

Holmium (Ho)

Erbium (Er)

Thulium (Tm)

Ytterbium (Yb)

Lutetium (Lu)

Scandium (Sc)

Yttrium (Y)

Rare-Earth Elements: Evidence of Metabolic Stimulation In Animals and Plants

Numerous studies across animal, plant, and microbial models (but NOT humans) show that the REE’s—particularly lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, and neodymium—have been shown to stimulate aspects of metabolism, often through improved growth, feed conversion, antioxidant effects, and altered gene expression.

However, we must recognize that the above results were dose and context-dependent and not uniformly positive (some trials showed no benefit or even growth suppression at higher doses).

Key Studies Include:

Rat study: Oral supplementation with lanthanum chloride or a mixture of rare earth chlorides (La, Ce, Pr, Nd) increased daily body weight gain, improved feed conversion ratio, and significantly enhanced blood enzyme activities (again, will become important later).

Piglet Study: Feeding with citrate-bound rare earth elements (mainly La, Ce, Pr, Nd) elevated thyroid hormones (T3, T4), well-established regulators of metabolic rate.

Review in livestock: In pigs, poultry, and rats, supplementation consistently produced greater weight gain, improved feed conversion, and faster growth rates—classic signs of increased metabolic efficiency and overall metabolic rate.

Plant studies: Exposure to REEs boosted enzyme activity involved in antioxidant metabolism and protein synthesis.

Recent mechanistic review concluded that REEs enhance enzyme and hormone activities, stimulate immune and digestive function, and promote metabolic processes such as protein and lipid metabolism in animals, depending on dose and element type.

Physiological and Practical Significance

One particularly fascinating aspect of REEs is that, as shown in the above animal studies, their physiologic effects were so significant that they attracted attention among animal nutritionists as potential growth promoters, despite legal prohibitions on the use of growth-promoting antibiotics in livestock diets!

Further, I hypothesize that the “epigenetic” (gene-activating) mechanisms identified in the animal studies above may also be relevant to humans (if we ever study that). Such mechanisms are also supported by studies in bacteria, which demonstrate that multiple lanthanides directly alter the expression of up to 41% of genes—including those involved in carbohydrate, amino acid, and polyhydroxyalkanoate metabolism —indicating broad metabolic regulatory effects.

In summary, rare earth elements —especially lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, and neodymium—have repeatedly demonstrated the ability to stimulate metabolism and metabolic efficiency in animals, plants, and microbes. These effects arise primarily through:

increased enzyme activity

hormone modulation

upregulation of growth- and metabolism-related gene expression

The Global Human Cost

From a 2024 review:

“Micronutrient deficiencies are the leading cause of premature deaths, morbidity, and retardation in the physical and mental growth of children; in 2017, 11 million deaths and 255 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) could be attributed to malnutrition.”

This issue isn’t localized to the U.S., but it presents one of the most significant challenges humanity faces. The urgency is apparent: In this comprehensive update of interventions aimed at reducing undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies in women and children across the world, they predicted that, at best, the current total of deaths in children younger than 5 years could drop by 15% if populations were able to access just ten evidence-based nutrition interventions at 90% coverage.

Executing such interventions across low- and middle-income countries is optimistic, and, in my view, the projected gains are underwhelming. However, one goal of this book is to point toward a more fundamental, systems-level solution—one rooted in restoring the mineral foundation of human nutrition.

Minerals and Aging

Worse still, according to this review, the absorption of many vitamins and minerals declines with age. Certain diseases occur because people have difficulty absorbing nutrients; when they lack minerals, the problem is exacerbated. As the body ages, the process of assimilation slows, and the immune system becomes weaker. Exertion, stress, and exposure to environmental pollution further increase our requirements for minerals—especially zinc, calcium, and iron (again, largely the ones we most study).

Illustrative Example: Trace Mineral Erosion in Livestock

Although detailed in a 2021 study, Elmer Heinrich related that old-time cattle ranchers were already aware of mineral depletion. Fifty years ago, cattle thrived due to the superior quality of their feed; no supplements were required.

Today, cattle raised on current feed quality must be supplemented or they will be malnourished, become stunted, sickly, lose their hair, and abort their calves—all because of mineral deficiencies in the soil. I can’t help but wonder if the trajectory of cattle health may offer insights into our own?

Next: Chapter 4 - The Blind Spot in Mineral Science: What We Never Measured, We Never Knew

Upcoming Book Publications

Yup — not one, but two books are dropping from yours truly. At the same time? What?

From Volcanoes to Vitality: if, instead of this Substack version, you prefer the feel of a real book—or the smell of paper—or like to give holiday gifts, pre-order my grand mineral saga, shipping before Christmas.

The War on Chlorine Dioxide: if you want to read (or gift) another chronicle of suppression, science, and survival, grab the sequel you didn’t see coming—shipping mid-January. On this one, I say: buy it before they ban it. Hah!

© 2025 Pierre Kory. All rights reserved.

This chapter is original material and protected under international copyright law. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author

This makes me think about:

I visited Cartagena, Colombia a couple years ago. Was my first time back since being an exchange student there in 1978. Lived there for 3 months.

The food there was SO good. And it was hard to say exactly why that was. But you didnt even feel the need to use dressing on your salad - everything just tasted so good. My daughter said, “it’s like I didnt eat a preservative for a week. “

Now i’m thinking, it wasnt just that everything was so fresh — I bet their soil is much less depleted than ours.

When we lived in Tennessee I was getting my produce from a regenerative farmer who had been doing it for years. Best produce ever. His butternut squash was as orange as pumpkins skins. So sweet I used them for pie.