Where Our Drinking Water Comes From

Modern drinking water originates from surface and groundwater sources that are presumed clean but are increasingly shaped by legacy contamination, delayed exposure, and system design.

Sources of Drinking Water

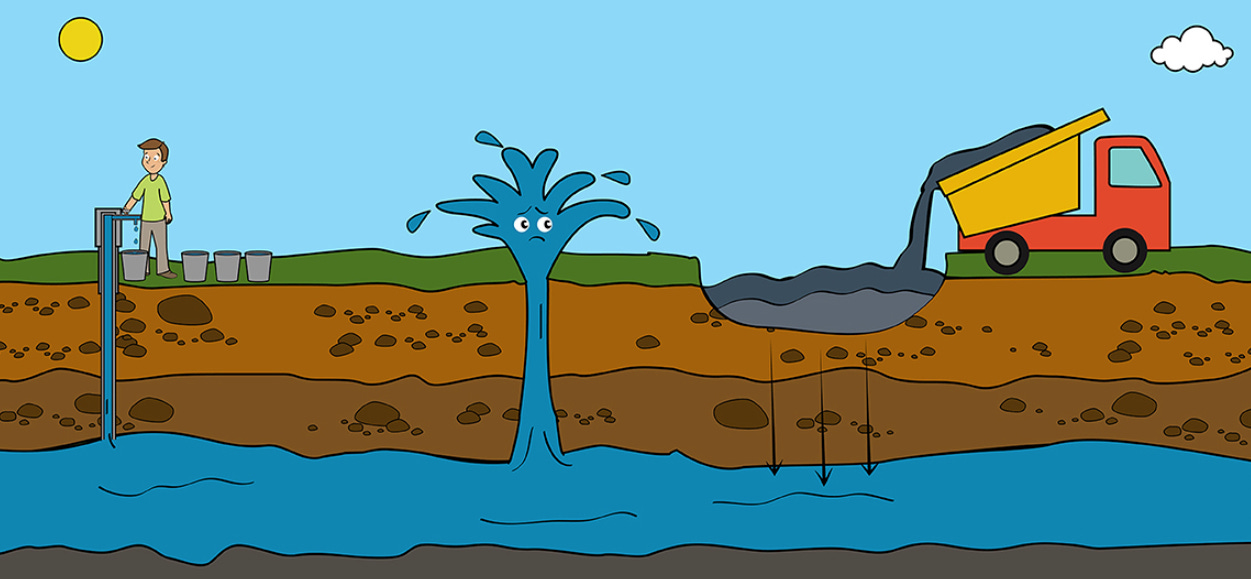

There are essentially two sources; “surface” and “ground.” Surface water refers to water from lakes, rivers, and reservoirs. Groundwater refers to a porous, chemically active, slowly moving system composed of fractured rock, sand, gravel, and clays which occur at various depths underground (see below):

As of 10 years ago, approximately 61% of municipal water was surface water, and the rest was groundwater. Public water is relied upon by 87% of Americans, with the rest drinking from private wells (i.e., private groundwater). Unfortunately (or fortunately as you will read about in a later posr), in either case, a very small number of public water utilities employ Reverse Osmosis systems.

So, which is better, the river above or the well below?

The answer, my friends, is neither.

The U.S. faces two overlapping water quality challenges:

Surface water pollution is widespread, complex, and traditionally managed through treatment systems that are literally designed to not fully remove all possible contaminants. This affects many major drinking water sources. The problem with groundwater contamination is that it is pervasive in certain regions and difficult to detect and even more difficult to remediate.

Let’s go deeper, starting in the ground (obviously) and then come up to the surface.

Groundwater — The Myth of the Pristine Aquifer

Most Americans apparently have a perception that groundwater from aquifers is somehow protected by depth, rock, and time, making it seem like aquifers are natural vaults, sealed off from the mess we make at the surface.

An aquifer is not a lake. It is a porous, chemically active, slowly moving system composed of fractured rock, sand, gravel, and clays through which water migrates at rates measured not in feet per second, but often in feet per year. Whatever enters that system does not flush out. It accumulates, stratifies, reacts, and lingers.

About three months ago, after deploying sulfated biotite mineral complexes in my practice, I feel like I changed my specialty from “pulmonary and critical care” to “mineralogy and hydrology,” because the way in which I perform history-taking has drastically changed, “What is the source of your household drinking water, do you remineralize, what kind of filter do you use etc.”

The patients with private wells really do tend to answer both proudly and confidently. I am now learning that they shouldn’t be, because the story of private well is not a good one.

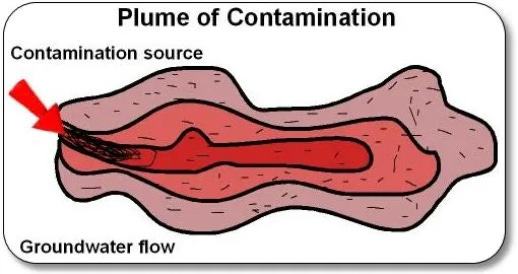

What The Heck Is A Plume?

I found this aspect of groundwater contamination somewhat fascinating. My thought was that when an aquifer gets contaminated, the contaminants diffuse uniformly, but instead, they form “plumes,” like smoke plumes in air, or an ink dye in water. Further, they elongate in the direction of flow and given how slow the water moves down there (feet per year), they result in long, tapering bodies of contamination - a plume.

Shockingly, plumes can often last decades… to centuries. Reason being is that groundwater moves too slowly for natural flushing to clear them on human time scales (insert “bug eye” emoji).

Plume Avoidance

Plume avoidance is a quiet but revealing admission built into modern water management. It recognizes that once contamination enters an aquifer, it often cannot be fully removed in any meaningful timeframe. Groundwater moves slowly, contaminants move with it, and many industrial chemicals persist for decades.

Rather than attempting to restore a polluted aquifer, plume avoidance focuses on preventing exposure by staying out of the plume’s path altogether. Wells are relocated, drilled deeper, or positioned up-gradient from known contamination. Water systems switch sources, alter pumping patterns, or legally restrict new wells from tapping compromised zones. The goal is not to clean the water, but to avoid intersecting contamination in the first place.

What makes plume avoidance so important is that most groundwater contamination does not cause dramatic poisoning events. Instead, it produces low-dose, chronic exposure that unfolds silently over years. By the time a plume is detected at a wellhead, the exposure has already occurred. Plume avoidance accepts this reality and shifts strategy upstream, away from treatment at the tap and toward source protection through distance, depth, and geology. In doing so, it quietly acknowledges a hard truth modern water systems rarely state plainly: some water sources are no longer salvageable, and the safest response is not to fix them, but to stop using them.

The deeper I went into groundwater contamination, plume behavior, delayed exposure, and the “quiet” inadequacy of existing treatment strategies, the harder it became to pretend that pointing out the problem was enough.

Enter Aurmina

I can understand why some readers may see these water posts, excerpted from my 35 chapter book, “From Volcanoes To Vitality,” as self-serving, given that I recently started a company that sells a mineral-based water purification product called Aurmina. I won’t argue with that reaction. All I can say is that my entry into this space came after the research, not before it, and after realizing that the water my patients were drinking was subject to the same structural failures I was documenting.

When institutions quietly accept that some water sources are no longer fixable, responsibility shifts to the individual. At that point, each person has to decide how seriously they take the integrity of the water they drink. Aurmina exists as one way to act on that responsibility.

Depth Is Destiny: The Hidden Gradient of Water Contamination

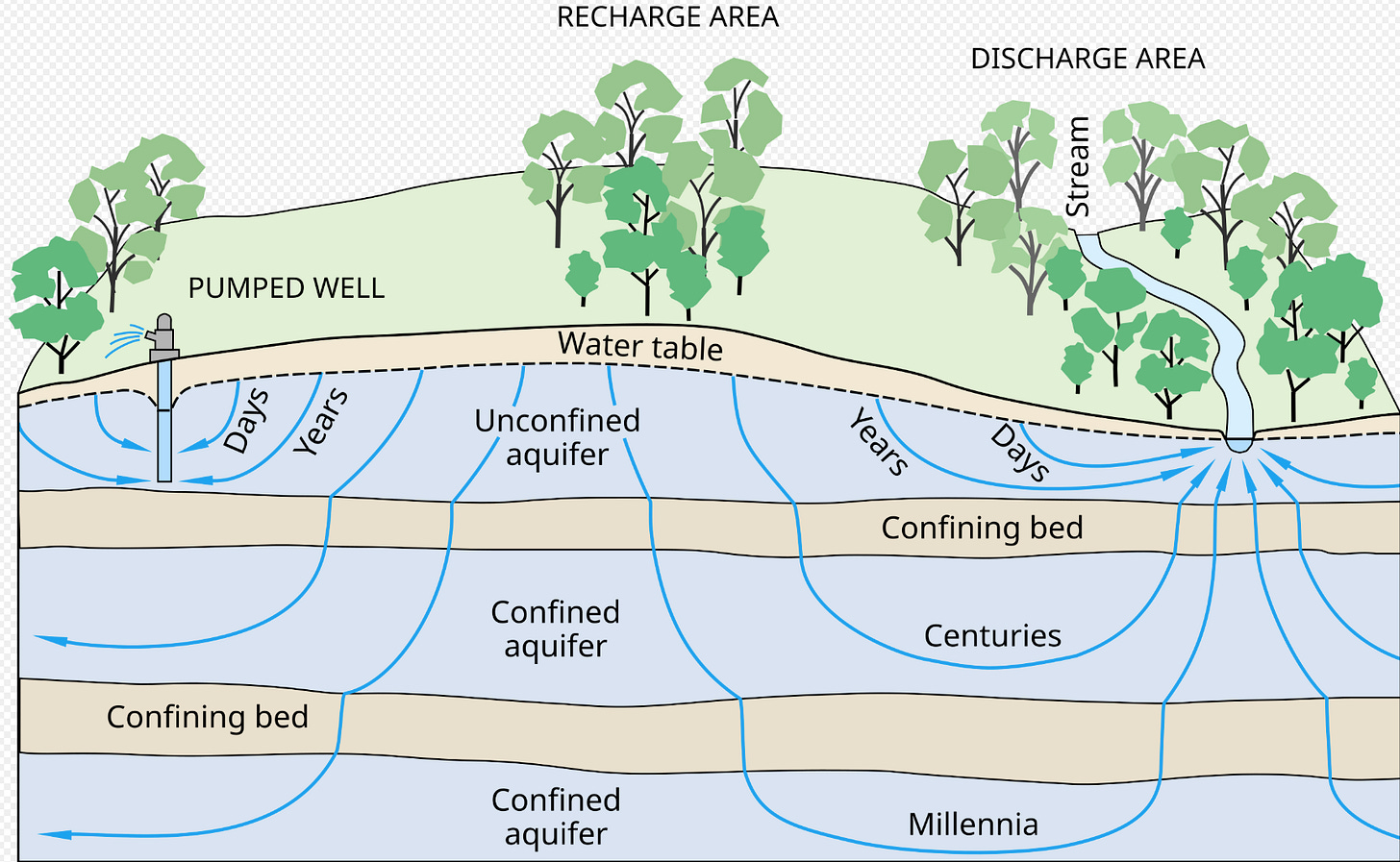

The quality of groundwater is not uniform. It changes dramatically with depth, and that vertical gradient largely determines how vulnerable a water source is to contamination. In general, the deeper the water, the older it is, the slower it moves, and the more insulated it is from modern surface pollution. The problem is that most drinking water sources never reach truly protective depths.

Shallow Aquifers

typically between 10 and 150 feet, are the most vulnerable by far. These are the aquifers that supply the majority of private wells and many rural households. They are directly connected to the surface through permeable soils, fractured rock, and agricultural land.

Rainfall, fertilizer runoff, pesticides, septic effluent, fuel residues, PFAS, and industrial solvents can migrate into these aquifers with relative ease. Because recharge happens quickly, contaminants do not need decades to arrive—they can reach shallow groundwater within months or years.

This is why shallow wells are disproportionately affected by nitrate contamination, bacterial intrusion, and newer synthetic chemicals. They are not “failed” systems; they are simply too close to the surface to be protected.

Intermediate-depth aquifers

roughly 150 to 600 feet deep, supply many municipal and suburban water systems. These sources are often assumed to be safe simply because they are deeper and regulated, but depth alone does not confer immunity. While these aquifers are less exposed to direct surface infiltration, they are still vulnerable to slow-moving contamination plumes, historical industrial releases, and long-lived chemicals that migrate laterally through groundwater over decades.

Many of today’s PFAS detections, chlorinated solvent findings, and arsenic exceedances occur at these depths. The contamination may be dilute, intermittent, or just below regulatory thresholds, which allows it to persist unnoticed for years while still contributing to chronic exposure.

Deep, confined aquifers

extend from roughly 600 to 3,000 feet, and tend to be the cleanest in terms of modern industrial pollutants. These waters are often thousands to tens of thousands of years old and are geologically isolated by impermeable layers of clay or rock. Large municipal systems and drought reserves increasingly rely on them as surface and shallow groundwater quality declines. However, depth introduces a different class of problems.

Deep aquifers frequently contain elevated levels of naturally occurring metals such as arsenic, manganese, iron, and uranium, as well as higher salinity and dissolved solids. These are not signs of pollution in the conventional sense; they are the geochemical fingerprint of long water–rock interaction. Treating these waters requires aggressive chemical adjustment, blending, or desalination, which alters the water’s mineral balance even further.

The uncomfortable reality is that most Americans are drinking from shallow or intermediate aquifers because deep groundwater is expensive to access, slow to recharge, and legally constrained. Depth offers protection, but it is a scarce resource. Modern water systems operate largely within this constraint, drawing from sources that are close enough to the surface to be practical—and close enough to contamination to require constant monitoring, mitigation, and, increasingly, avoidance.

The Temporal Trap: Why Groundwater Pollution Is Delayed

What groundwater drinkers are drinking today is water that first encountered modern agriculture, industry, or waste streams decades ago. Nitrates applied to cornfields in the 1970s are still migrating down in parts of the Midwest. Chlorinated solvents dumped in the 1950s still form plumes beneath industrial sites today. PFAS released during Cold War firefighting exercises are now appearing in municipal wells for the first time.

One good thing about surface water is that problems there can respond quickly, in that if you spill something into a river, it moves downstream. Treat the source, and improvements can be measured in months or years.

The problem with groundwater is that aquifers respond slowly. This delay creates a dangerous illusion: by the time contamination is detected, the causative behavior often stopped years earlier, and the plume is already entrenched.

Well Water

When I talk to my patients about their water sources now, those with well water typically answer with what seems a quiet confidence, because on the assumption that if it comes from the earth it must be clean, stable, and protected.

In reality, that confidence is rarely earned. Private wells sit outside the regulatory net, are generally the shallowest depth, are often tested once and then forgotten, and draw from groundwater that faithfully dissolves whatever geology, agriculture, industry, or waste history it passes through.

The water may look clear and taste fine while carrying arsenic, nitrates, manganese, pesticides, PFAS, or microbial contaminants at levels that don’t cause acute illness but quietly shape biology over years and decades. Well water can be exceptional, but it can just as easily be a slow, unmonitored chemical experiment. Trusting it without regular, broad testing isn’t scientific; it’s hopeful.

Testing With Aurmina

I can happily report that I am currently in the mountains of Montana, at a house whose well is 1,200 feet deep! Unsurprisingly, given that it is mountain water, from Montana, and the well is one of the deepest you can find with a private house, I tested it with Aurmina… and it stayed clear! Check it out:

More Stuff (Aurmina and Book Publications)

If you value the late nights and deep dives into all the “rabbit holes” I write about (or the Op-Eds and lectures I try to get out to the public), supporting my work is greatly appreciated.

If you’re curious about the volcanic-mineral water purification product described above, you can find it at Aurmina.com. Think of it as a quiet act of restoration — starting with your water.

Know that not one, but two books are dropping from yours truly (at the same time?) What?

If, instead of (or in addition to) this Substack version, you prefer the feel of a real book—or the smell of paper—or like to give holiday gifts, pre-order From Volcanoes to Vitality, my grand mineral saga, shipping before Christmas.

And if you want to read (or gift) another chronicle of suppression, science, and survival, grab The War on Chlorine Dioxide—the sequel you didn’t see coming—shipping mid-January. On this one, I say: “Buy it before they ban it.” Hah!

This chapter is original material and protected under international copyright law. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author.

© 2025 Pierre Kory. All rights reserved.

Very informative analysis! Thank you!

We have allowed them to put systems in that completely contaminate our environment. Every day I see people totally uncaring and unaware of what they are doing in their everyday lives that contribute to the contamination - they run cars while they chat or pop into a store polluting the ground air, they buy plastic like there's no tomorrow, they spray poisons on their lawn proudly. Now if you're serious you want to clean the environment, we need to be talking about hemp over and over and over. But not a whisper. We ought to be putting together a structure where we incentivize, encourage and reward good care of the environment. I have put such a list together and it rewards people for such things as not having a car, not using pesticides, growing their own food organically, for putting out trash once a month rather than once a week, and many more. It attributes units or points to those who do these things. If anything it makes us all more aware of the damage WE DO OURSELVES by going along with what's most convenient. Once people would use the excuse that they're too busy, but now more people don't have jobs. Doing things in accordance with caring for the environment actually saves us a lot of time overall. But people are too stuck in their ways. Ugh.