Chapter 14E: The Cell’s Battery: Proton Gradients, Leaks, and Modern Stressors

How mitochondria make ATP—plus what toxins and EMFs do to the gradient (and how minerals help).

Not that I want you to do this, but if you are uninterested or unknowledgeable in the biochemical and metabolic pathways that I will elucidate in the following, again, I suggest skimming, or just outright skipping to Chapter 15 - “Minerals Made Simple: How Nature’s Elements Keep Water, Plants, and People Alive” This way you won’t get annoyed with me or complain that I am being too “scienc-ey.”

When I first began studying trace minerals for my patients, I assumed I was simply searching for missing nutrients. Yet as I delved deeper into the chemistry — from volcanic springs in Japan to my own clinic in the United States — I began to see something larger.

All life, from a sprouting seed to a beating heart, runs on the movement of protons. This subtle flow of charged particles across membranes is called a proton gradient, or proton motive force (PMF), and it is the invisible engine behind ATP, the molecule that powers every cell.

Trace minerals such as iron and sulfur aren’t just ingredients in this process; they are part of the very architecture that makes the engine run. Lightning, sunlight and volcanic ocean emissions on the early Earth created the same raw conditions that cells still use today.

My journey with Themarox and Shimanishi has been an introduction to this hidden current. In this chapter, I want to share how these insights unfolded for me, why they matter, and how we’re now building the next stage of research to explore them further.

Let’s start with the fact that every living cell relies on an internal “battery” to power everything it does (in my favorite organelle, the mitochondria). This battery is maintained by moving electrons (tiny negatively charged particles) through specialized proteins called the electron transport chain (ETC). Thus, the ETC is a mineral “electronic circuit,” converting redox (electron transfer) potential into biological work — powered by the rhythmic flow of electrons and protons across structured water layers within the mitochondrial membranes.”

However, this electron flow depends on a gradient—a difference— involving protons (positively charged hydrogen ions). This proton gradient across membranes drives the creation of ATP, the cell’s main energy carrier, much like water behind a dam generates electricity.

For decades, biology textbooks described this process as being driven primarily by the flow of electrons. Yet this description is incomplete. It overlooks the fact that the electrons’ energy is used to “pump protons” to one side of the membrane, creating the “proton gradient” itself. But as you will learn below, it is actually the proton gradient that moved the electrons in the first place—a concept known as the “the primacy of the proton gradient.”

Although they are also positively charged, the minerals listed above are not “protons” themselves. They are metal ions (cations)— larger and chemically distinct from protons.

How Electrons Move and What That Accomplishes:

Electron Donors: Electrons start their journey from carrier molecules such as NADH, FADH₂, entering the electron transport chain (ETC) at Complex I or II.

Progression: These electrons are passed from one complex’s minerals to the next via redox reactions—each a precisely controlled transfer, never random.

Release of Energy: Each transfer releases a small, usable amount of energy.

Proton Pumping and the Creation of a Gradient

The key point is how this released energy is used: Protein complexes use this energy to “physically” pump protons (H⁺ ions) from the mitochondrial matrix (the inside) across the inner membrane into the intermembrane space (the outside). “Pumping” means the protons are actively transported against both their concentration and electrical gradients—like moving water uphill into a reservoir.

“The protein complexes of the electron transport chain (ETC) are not composed solely of amino acids—they depend on a network of metal-containing cofactors such as iron–sulfur clusters, hemes (iron-based porphyrins), and copper centers. Together, these cofactors form a stepped redox gradient that allows electrons to flow through the chain, ultimately driving proton pumping across the mitochondrial membrane and generating the proton-motive force that powers ATP synthesis.

As I’ve emphasized before, this highlights the primal importance of minerals: nearly every metabolic enzyme, including those of the ETC, requires mineral cofactors not only to function but often to fold correctly, maintain structure, and enable catalysis. Without them, life’s bioenergetic machinery simply could not exist.”

How the process works:

The passage of electrons through complex machinery causes changes in the shape of these proteins, which power a kind of molecular lever that physically moves the protons to the other side. (Ah hah—a molecular lever at work!) More specifically, these ETC proteins are designed so that electron flow and proton pumping are spatially and temporally separated.

Electrons move through the membrane, while protons are moved across it, by tightly coupled but distinct mechanisms.

The Role Of Minerals

Mineral ions serve as essential cofactors embedded within protein complexes. Their functions include:

Facilitating electron transfer between redox centers, and

Stabilizing the protein structures that couple electron flow to proton movement (essentially, stabilizing the “molecular levers”).

Without these ions, the ETC cannot transfer electrons effectively , nor can the membrane proteins change their conformations to pump protons efficiently to maintain the gradient.

The Battery Analogy:

As protons (which are positively charged) accumulate outside the inner mitochondrial membrane, the matrix inside becomes more negative (since electrons are still entering). The intermembrane space, by contrast, becomes more positive. Together, this separation of charge and concentration creates an electrochemical gradient (umm, not just “an electrochemical gradient”, but THE electrochemical gradient which both sparks and maintains all life forms).

The result is, quite literally, a “charged battery” across the inner mitochondrial membrane:

Voltage (electrical potential): More positive outside, more negative inside.

Chemical concentration: More protons—and therefore a lower pH—outside than inside.

Final Step:

Protons naturally want to flow back down their gradient into the matrix —like water rushing back through a dam. However, they can only return through one specific gateway: the ATP synthase complex. This molecular turbine captures the energy of the returning protons to synthesize ATP, the universal energy currency of the cell. Voila!

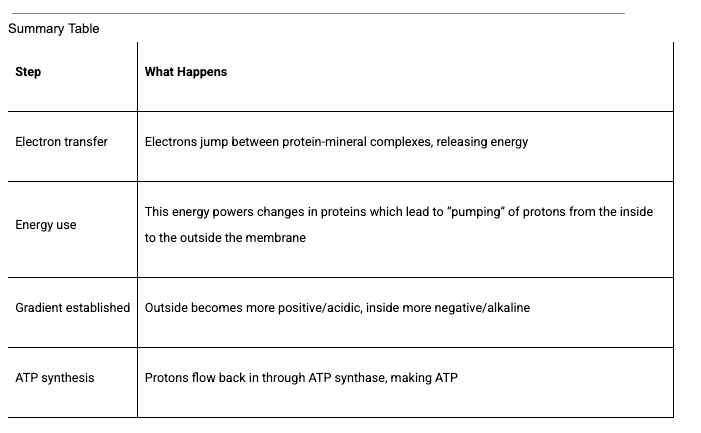

See table:

OK, so you thought you got through it and we’re all done now, eh? Not.

Sulfur Rears It’s Head.. Again

You see, in the list of mineral ions we detailed above, sulfur was not included—and yet sulfur is one of the most important elements. Its significance in both the creation of life and energy production through the electron transport chain (ETC) cannot be overstated.

The reason it wasn’t mentioned earlier is that sulfur plays a unique role—not as a cation—but as a critical structural and redox element within “iron-sulfur (Fe–S) clusters.” (In biological systems, sulfur does not exist as a free cation like S²⁺).

These Fe–S clusters act as relay stations for electrons, anchoring the other mineral ions in precise configurations that enable both rapid electron transfer and proper protein folding. More specifically, sulfur provides a structural framework that positions iron atoms exactly where they need to be. As such, sulfur clusters are among the most important cofactors in the entire ETC.

The combination of iron and sulfur—not the ions independently—is what enables highly efficient and rapid electron transfer required for cellular energy processes. Without both metal cations and sulfur, the ETC fails.

Interestingly, Themarox contains notably high amounts of iron sulfate, a characteristic that Shimanishi felt represented the “optimal composition” he was looking for when he searched the world for the most potent source of black mica.

A Novel Paradigm: The Primacy of Protons in Biological Energy

The number of protons in an atom’s nucleus is what differentiates one element from another on the periodic table. This fundamental property sets the stage for life by anchoring electrons—since electrons themselves are only stable because of this positive proton charge.

Although electrons transfer between molecules to drive redox reactions, their movement—and therefore all energy flow—is ultimately governed by the proton’s electrostatic potential.

Again from earlier, during energy production in mitochondria (and in chloroplasts in plants), electrons are passed along a chain of carriers, releasing energy that is then used to pump protons across a membrane, forming a proton gradient.

This gradient, known as the proton motive force (PMF), acts as a molecular “battery,” storing potential energy that drives the formation of ATP and powers vital cellular function.

Recall from Chapter 13, Section 4, TDS measures the total amount of dissolved ionic species (cations and anions) in water, while EC measures how easily electrical current (electrons) moves through that ionic medium.

The importance of this is that electrons don’t move through pure water — they only can move through ionic charge networks maintained by protons. The dissolved ions (minerals) in solution set up an electrostatic field — essentially, a proton–ion gradient.

That gradient determines the mobility of charges, which is what EC measures.

In summary, TDS quantifies the capacity for charge flow (how many minerals/ions are available). EC quantifies the efficiency of charge flow (how freely those ions conduct current). Both depend on proton–mineral interactions, just as biological redox flow does.

Thus, minerals play a foundational role in maintaining this system. Elements such as iron, sulfur, copper, magnesium, and zinc are required to build and stabilize the protein complexes that move electrons and pump protons. Without these minerals, the machinery breaks down: electron flow becomes unstable, and harmful free radicals form instead of useful energy.

Now, most importantly for this discussion, is that even if electron flow temporarily halts, a proton gradient can persist, holding stored energy within the membrane. Conversely, without that proton field, sustained electron transfer and redox cycling become energetically impossible—and energy production ceases almost immediately.

In summary, while electrons serve as the vehicle for energy transfer, it’s the stable, mineral-matrix supported proton gradients that provide life’s true energetic foundation. Without the proton gradient that the mineral matrix supports, cells cannot sustain the energy flows fundamental to all living systems.

Biological Implications of Mineral Balance

Mineral deficiency—whether from diet or environmental factors—can disrupt the body’s ability to maintain stable proton gradients. When these gradients destabilize, several consequences follow:

Disrupted energy production (lower ATP output)

Increased oxidative stress (cellular “rust”)

Reduced efficiency of repair and regulation mechanisms

Conversely, adequate mineral balance appears to correlate with more stable proton gradients, balanced redox behavior, and efficient energy coupling in biological systems.

Big Picture: From the Origins of Life to Modern Biology

Life first emerged in mineral-rich waters, where spontaneous proton and mineral gradients formed—essentially the first “batteries” of life— long before complex cells evolved.

Even today, these same physical principles operate in every living organism: mineral scaffolding supports proton gradients, and proton gradients drive the controlled flow of electrons that power all metabolic processes.

Reframing biology through the lens of “proton–mineral primacy” shifts the emphasis away from electrons and oxidative stress, and toward understanding the stabilizing role of minerals in maintaining charge balance and energy transfer.

Rather than viewing mineral ions and protons as mere byproducts of electron flow, they form the foundation upon which all cellular energy—and life itself— depends. Sustaining adequate mineral balance isn’t just about preventing deficiency; it’s about maintaining the integrity of the body’s most fundamental energy systems. When those systems destabilize, cellular efficiency declines. When they are restored, so is the capacity for normal biological resilience.

“Proton Leakage” — How Environmental Toxins Affect the Proton Gradient

“Proton leakage” occurs when protons re-enter the mitochondrial matrix through an alternative pathway from the ATP synthase pathway. This process, also called membrane uncoupling, results in proton flow without ATP generation (oh no!).

There are both physiologic and non-physiologic (toxic) causes of “proton leakage.”

Normal, Physiologic Proton Leakage

Uncoupling proteins (UCP1 in brown fat, UCP2/3 in other tissues) allow a controlled proton leak to generate heat and prevent the buildup of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Thus, a small baseline leak through the lipid bilayer helps fine-tune ATP production by preventing the electron transport chain from becoming over-reduced (i.e. too many electrons).

Interestingly, certain plants, like skunk cabbage, use mitochondrial uncoupling to generate heat, to melt snow and attract pollinators. Proton-leak driven thermogenesis, therefore, is a cross-kingdom adaptation.

In humans, “controlled” proton leak can also serve as a fine regulatory mechanism. While brown fat uses it to add warmth in the cold, most body heat comes from metabolic activity in muscles and organs, where increased ATP production naturally generates heat.

In short, protons themselves aren’t the thermostat—the regulated leak of the proton gradient is the body’s built-in way to modulate temperature and prevent oxidative overload.

Toxic/Pathological Leakage:

However, a number of chemical compounds (e.g., dinitrophenol, FCCP) act as protonophores, dramatically increasing leakage. Lipid peroxidation or membrane damage from heavy metals, pesticides, or other toxins can disrupt membrane integrity and increase proton leak. Another piece to the non-wellness puzzle eh? Chronic oxidative stress or mitochondrial mutations may also increase nonspecific leak.

The point is this: toxicity can trigger or worsen proton leakage, but leakage itself is not automatically a sign of toxicity—it’s a normal physiological phenomenon at low levels as described above.

A list of commonly recognized protonophores includes:

2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP)

FCCP (carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone)

CCCP (carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone)

FCCP (carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone)

Pentachlorophenol (PCP)

Usnic acid

Triclosan

Niclosamide

Pyrrolomycin

Indole

These compounds shuttle protons via non-ATP synthesizing pathways, dissipating the proton gradient and uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation.

If you did not recognize several of the compounds listed above, that is likely because some are rare in the environment, but others are far more common.

Consequences of Excessive Proton Leakage:

Mitochondria: Lower ATP yield, potential energy deficit.

ROS cascades: If the proton gradient collapses too far or the electron transport chain becomes overly reduced, more superoxide and hydrogen peroxide (i.e. ROS) may form.

Metabolic shifts: Cells may increase glycolysis or activate stress pathways to compensate.

In plants, similar leakage in chloroplasts can lower photosynthetic efficiency; in bacteria, it can reduce growth rates or shift metabolic products. Thus, proper mineral stores for humans, animals, and plants are needed to maintain optimal proton gradients and energy production, but are also needed to defend the proton gradient against leakage induced by environmental toxins and/or oxidative stress.

Electro-Magnetic Field (EMF) Pollution and Proton Leakage

Beyond the accumulating toxins, heavy metals and pollutants in our soils and waters (the latter is covered later in this book), growing attention is being given to the effects of electromagnetic fields (EMF).

EMF is a colloquial term for the ever increasing amount of man-made electromagnetic fields which are viewed as environmental “pollution” or “electrosmog.” They are ubiquitous in modern life—emitted by power lines, household electricity, wireless devices, and mobile networks. More than three billion people worldwide are exposed to some form of EMF daily, and those levels continue to rise with rapid expansion of technologies such as 5G.

The reason I bring this up here is because elevated EMF exposure can interfere with the mitochondrial proton-motive force we have been discussing. Research indicates that EMFs can increase proton leak, alter ion transport, and disrupt membrane potential, leading to partial uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation. These changes may contribute to heightened oxidative stress, shifts in energy dynamics, and, if exposure is prolonged, tissue-level stress responses.

One study in human peripheral blood monocytes reported increased resting oxygen consumption, greater proton leak, and altered redox balance following EMF exposure—implicating disruption of mitochondrial PMF as a central mechanism.

This study found that these mitochondrial disturbances may contribute to neurodegenerative diseases, cancer, and increased cellular stress responses. Another study linked chronic EMF exposure to a spectrum of biological effects, ranging from cognitive and fertility impacts to signs of accelerated cellular stress.

However, it’s important to note that the above research is hypothesis-generating only and research in this field remains inconclusive.

Many studies are preliminary, vary in methodology, and sometimes produce conflicting results. More controlled, long-term investigations are needed to clarify whether EMFs directly cause these mitochondrial changes, or if the observed effects are adaptive rather than harmful.

From both personal observation and experience, I’ve known people—some of them my patients—who are particularly sensitive to EMFs, to the point of relocating to remote, rural areas to lessen their exposure and maintain “wellness.”

I think I’m going to discuss with these patients the importance of maintaining adequate mineral status to support normal mitochondrial function—particularly ensuring sufficient intake of key minerals like iron and sulfur, and addressing any documented deficiencies.

Wrap-Up: Where the Story of Water Becomes the Story of Life

So here’s the simple, astonishing takeaway from all this science:

First, clean the water. Remove what doesn’t belong — the toxins, the plastics, the residues that choke its charge. Then, bring it back to life. Give it the minerals that let it breathe, structure, and conduct energy.

It’s the same dance from pond to proton:

Environmental minerals purify the external world.

Biological minerals power the internal one.

Same minerals. Same laws of physics. Different stage.

Themarox, Shimanishi, Pollack—they all point to the same truth: the vitality of water and the vitality of life share the same mineral root.

We purify to prepare. We remineralize to sustain.

Because minerals aren’t drugs or additives — they’re the hardware of existence, the physical circuitry that keeps energy flowing and life self-organizing.

Clean the medium. Rebuild the matrix.

That’s how life stays charged.

P.S. If you’re curious about the volcanic-mineral water purification product that this book led me to help develop, you can find it at Aurmina.com. Think of it as a quiet act of restoration — starting with your water. And yes, I know — I’ve become the guy who includes links at the end. But this one just might change your water (and your mind)

.

© 2025 Pierre Kory. All rights reserved.

This chapter is original material and protected under international copyright law. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the author.

Chapter 15 - Laypersons Summary - Minerals Made Simple: How Nature’s Elements Keep

"Clean the medium. Rebuild the matrix.

That’s how life stays charged."

There's your mic drop!!!

Thanks for your work! It seems to me, after reading this chapter, like the connection to mitochondria is an especially key link between what we lack in minerals and what we lack in health.

Mitochondrial disruption or malfunction has been linked, as I have come to understand, to a variety of maladies, including cancer, Alzheimer’s, and COVID/COVID vaccine injuries.

I know of your work in two of these areas, so this leads me to ask: is there more coming for the lay audience about the big connections across your work? I could envision an article pulling it all together: “mitochondria, metabolism, and minerals.” Or something like that!